Gitanjali

Rabindranath Tagore's Nobel Prize-winning collection of devotional poems exploring the relationship between humanity and the divine.

Gallery

Gallery

Title page of Gitanjali, the collection that brought Tagore international acclaim

Title page of the English edition published by Macmillan and Company, London, 1912

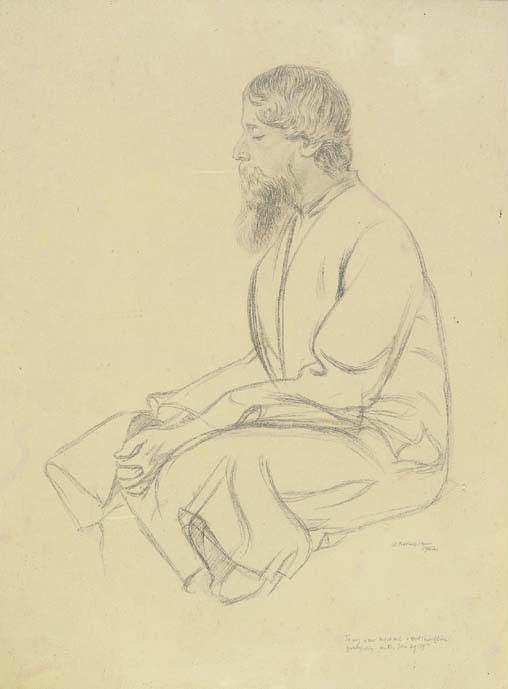

Portrait of Rabindranath Tagore by William Rothenstein, created around the time of Gitanjali's publication

Introduction page featuring William Rothenstein's artistic contribution

Introduction

In the annals of world literature, few works have achieved the transformative cultural impact of Gitanjali (গীতাঞ্জলি), a collection of devotional poems that bridged Eastern spirituality and Western literary sensibility. Published on August 4, 1910, this Bengali masterpiece by Rabindranath Tagore represents a profound meditation on the human soul’s relationship with the divine, expressed through lyrical verses that blend mysticism, nature imagery, and philosophical introspection. The work’s original title translates to “Song Offerings,” aptly capturing its essence as spiritual offerings rendered in poetic form.

When Tagore’s self-translated English version appeared in 1912, it catalyzed a seismic shift in global literary consciousness. The following year, in 1913, the Swedish Academy awarded Tagore the Nobel Prize for Literature “because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West.” This unprecedented recognition made Tagore the first non-European, the first Asian, and remains to this day the only Indian to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature—a watershed moment that challenged Eurocentric literary paradigms and introduced millions to the richness of Indian spiritual and poetic traditions.

Gitanjali emerged during the Bengal Renaissance, a period of extraordinary cultural, social, and intellectual ferment in colonial India. The work embodies the syncretic vision characteristic of this era, drawing from ancient Bhakti traditions, Vaishnava mysticism, Upanishadic philosophy, and the poet’s own Brahmo Samaj background, while simultaneously engaging with Romantic and Victorian literary influences. This 104-page volume represents more than a collection of poems; it stands as a testament to the universality of spiritual longing and the transcendent power of poetry to communicate across cultural boundaries.

Historical Context

The creation of Gitanjali occurred against the backdrop of British colonial India at the height of the Bengal Renaissance, a period roughly spanning from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century. This intellectual and cultural movement sought to reconcile traditional Indian values with modern Western thought, producing remarkable achievements in literature, art, science, and social reform. Bengal, particularly Calcutta (now Kolkata), served as the epicenter of this renaissance, attracting intellectuals, artists, and reformers who questioned orthodoxies while celebrating India’s cultural heritage.

Rabindranath Tagore belonged to the illustrious Tagore family, themselves central figures in this cultural awakening. His grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, was a pioneering industrialist and social reformer, while his father, Debendranath Tagore, led the Brahmo Samaj, a reformist Hindu movement that rejected idol worship and caste distinctions while embracing monotheism and rational inquiry. This intellectual environment profoundly shaped Tagore’s worldview, instilling in him a spiritual orientation that transcended sectarian boundaries while remaining rooted in Hindu philosophical traditions.

By 1910, when Gitanjali was first published in Bengali, Tagore had already established himself as Bengal’s preeminent literary figure, having produced numerous volumes of poetry, novels, short stories, and plays. The early 20th century witnessed intensifying nationalist fervor in India, with the Partition of Bengal (1905) and the Swadeshi movement galvanizing anti-colonial sentiment. While Tagore supported Indian independence, his vision emphasized cultural renaissance and international humanism over narrow nationalism—themes that permeate Gitanjali’s universal spiritual concerns.

The devotional poetry tradition from which Gitanjali draws has deep roots in Indian literary history. The Bhakti movement, which flourished from the 7th to 17th centuries across various regions of India, emphasized personal devotion to the divine and produced an extraordinary corpus of vernacular poetry. Medieval Bengali Vaishnava poets like Chandidas, Vidyapati, and the Baul folk tradition particularly influenced Tagore, as did the medieval Hindi poet Kabir and the Marathi saint-poet Tukaram. Gitanjali thus represents a modern synthesis of these devotional traditions, filtered through Tagore’s cosmopolitan sensibility and expressed in the refined literary Bengali he helped standardize.

Creation and Authorship

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) composed the original Bengali Gitanjali during a period of intense creative productivity, completing it in 1910 when he was 49 years old. By this time, Tagore had experienced profound personal losses, including the deaths of his wife Mrinalini Devi in 1902, his daughter Renuka in 1903, and his youngest son Samindranath in 1907. These bereavements deepened the spiritual introspection evident in Gitanjali, lending the poems an authenticity born of genuine existential questioning and spiritual seeking.

The creative process behind Gitanjali reveals Tagore’s working methods and artistic philosophy. He composed the poems in Bengali, the language in which he could achieve maximum lyrical expressiveness and emotional nuance. The Bengali version contained 157 poems, carefully structured and arranged to create a devotional arc moving from earthly consciousness toward divine union. Tagore drew inspiration from his daily life at Santiniketan, the experimental school and community he founded in rural Bengal, where natural beauty and spiritual contemplation shaped his daily routine.

The transformation of Gitanjali into its English avatar occurred somewhat serendipitously. In 1912, while traveling to England, Tagore fell ill during the journey and began translating some of his Bengali poems into English prose-poetry to pass the time. These were not literal translations but rather creative re-imaginings that sought to capture the essence and emotion of the originals while adapting to English literary sensibilities. The English Song Offerings drew from the Bengali Gitanjali but also incorporated poems from other Bengali collections, including Gitimalya, Naivedya, and Kheya.

Upon arrival in London, Tagore showed his manuscript to the painter William Rothenstein, who was struck by their beauty and immediately shared them with W.B. Yeats, then at the height of his powers as a poet. Yeats was profoundly moved, reportedly reading them aloud to audiences and writing an enthusiastic introduction to the published volume. Yeats’s introduction, praising the poems’ “intensity of passion” and describing them as having brought his “own thoughts to stillness,” proved instrumental in the work’s reception. The India Society published a limited edition in September 1912, followed by Macmillan’s commercial edition in March 1913, just months before the Nobel Prize announcement.

Content and Themes

Gitanjali explores the multifaceted relationship between the human soul and the divine, rendered through poems that vary in mood from ecstatic celebration to anguished longing. The central metaphor throughout the collection presents the divine-human relationship as that between lover and beloved, a convention drawn from Vaishnava devotional traditions where Krishna represents the divine beloved. However, Tagore universalizes this framework, stripping away specific mythological references to create a more abstract, accessible spiritual landscape.

The opening poem establishes the collection’s devotional framework: “Thou hast made me endless, such is thy pleasure. This frail vessel thou emptiest again and again, and fillest it ever with fresh life.” This invocation introduces several key themes: divine grace as the source of human creativity, the soul as a vessel for divine expression, and the cyclical nature of spiritual renewal. The poem’s tone combines humility with exaltation, positioning the speaker as a willing instrument of divine will.

Throughout the collection, Tagore employs nature imagery as a bridge between material and spiritual realms. Dawn, sunset, flowers, rivers, and seasonal changes become vehicles for exploring spiritual states. In one celebrated poem, he writes: “The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures.” This pantheistic vision, reminiscent of Upanishadic philosophy, sees the divine immanent in nature rather than transcendent and separate.

The theme of spiritual longing pervades many poems, expressed through the metaphor of waiting and seeking. The speaker repeatedly describes preparing for a divine encounter that remains tantalizingly just beyond reach: “I have had my invitation to this world’s festival, and thus my life has been blessed. My eyes have seen and my ears have heard.” This tension between presence and absence, fulfillment and longing, creates the emotional dynamism that animates the collection.

Social consciousness occasionally surfaces within the predominantly spiritual framework. Several poems critique religious ritualism and social hierarchy, reflecting Tagore’s Brahmo Samaj background and his commitment to social reform. One poem declares: “Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads! Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark corner of a temple with doors all shut? Open thine eyes and see thy God is not before thee!” This prophetic voice challenges empty religious observance while advocating for finding the divine in human service and everyday life.

The collection also explores the creative process itself, presenting artistic creation as a form of spiritual practice. Tagore frequently uses musical metaphors—the divine as musician, the soul as instrument—to explore how human creativity participates in divine expression. This meta-poetic dimension adds intellectual depth to the devotional framework, suggesting that poetry itself constitutes a spiritual discipline.

Artistic Analysis

Tagore’s poetic technique in Gitanjali demonstrates masterful control of both Bengali versification and, in his self-translations, English prose-poetry. The Bengali originals employ traditional meters and rhyme schemes drawn from classical Sanskrit poetry and medieval Bengali devotional songs, while incorporating the more colloquial vocabulary and syntax that Tagore pioneered in modernizing Bengali literary language. His innovations helped establish a Bengali poetic idiom that balanced formal sophistication with emotional accessibility.

The English versions adopt a quite different aesthetic approach. Rather than attempting to reproduce Bengali metrical patterns, which would have resulted in awkward or stilted English, Tagore chose rhythmic prose-poetry reminiscent of the King James Bible and Walt Whitman’s free verse. This decision proved aesthetically and commercially astute, as Edwardian readers found the biblical cadences familiar yet exotic, spiritual yet accessible. The resulting style, with its incantatory repetitions and parallel structures, creates a meditative atmosphere conducive to spiritual contemplation.

Tagore’s imagery draws extensively from the natural world, particularly the landscape of Bengal with its rivers, monsoons, mango groves, and agricultural rhythms. However, he employs this imagery symbolically rather than descriptively, using natural phenomena as objective correlatives for spiritual states. A storm might represent divine power overwhelming human consciousness; a lamp suggests the soul’s persistent light amid darkness; flowers symbolize offerings of devotion. This symbolic method allows readers from different cultural contexts to access the poems’ emotional and spiritual content without requiring specific knowledge of Bengali geography or culture.

The poems’ structure often follows a dialectical pattern, moving from statement to questioning to resolution or, alternatively, from description of separation to longing for union. This structure mirrors the spiritual journey from ignorance to enlightenment, from separation to union with the divine. The collection as a whole lacks strict linear narrative but creates an emotional and spiritual arc through careful sequencing, moving through various moods and spiritual states.

Tagore’s use of paradox reflects the influence of mystical traditions worldwide, which often employ contradictory language to point toward transcendent realities beyond logical discourse. He writes of finding fullness in emptiness, freedom in surrender, immortality in death. These paradoxes challenge rational thought while inviting intuitive understanding, a technique characteristic of both Hindu Vedantic philosophy and Sufi mysticism.

Cultural Significance

Gitanjali occupies a unique position in Indian cultural history as perhaps the single work that most successfully introduced Indian spiritual and literary traditions to global audiences. Prior to Tagore’s Nobel Prize, Indian literature remained largely unknown in the West, except through often-inadequate translations and orientalist scholarly works. Gitanjali demonstrated that Indian literary art could achieve the same aesthetic sophistication and emotional depth as Western poetry while offering distinctive spiritual perspectives rooted in Indian philosophical traditions.

Within India itself, Gitanjali contributed to the cultural nationalist project of the Bengal Renaissance by demonstrating that Indian cultural production could command international respect. Tagore’s Nobel Prize provided immense psychological validation for Indians during the colonial period, suggesting that Indian civilization could contribute to world culture on equal terms with European traditions. This significance transcended purely literary concerns, bolstering arguments for Indian self-governance and cultural autonomy.

The work’s devotional framework resonated particularly strongly with Indian readers already familiar with Bhakti traditions. While Tagore’s sophisticated literary technique and philosophical complexity appealed to educated elites, the poems’ emphasis on direct spiritual experience over religious ritual and their use of everyday imagery made them accessible to broader audiences. Gitanjali helped demonstrate that modern literature could express spiritual concerns without abandoning artistic innovation or intellectual rigor.

Religious communities within India responded to Gitanjali with varying degrees of enthusiasm. The Brahmo Samaj naturally embraced it as an exemplary expression of their reformist monotheism. More orthodox Hindu communities sometimes viewed Tagore’s universalism and rejection of idol worship with suspicion, though many could appreciate the poems’ debt to classical Hindu philosophy and medieval devotional poetry. The work’s non-sectarian spirituality also appealed to those seeking alternatives to organized religion, contributing to modern Indian spiritual movements emphasizing personal experience over institutional authority.

Influence and Legacy

The impact of Gitanjali on world literature and Indian letters cannot be overstated. Its success paved the way for subsequent Indian writers seeking international recognition, establishing precedents for how Indian literature might be translated and presented to global audiences. Writers across Asia drew inspiration from Tagore’s achievement, seeing in it proof that non-European literatures deserved serious critical attention and could succeed in international literary marketplaces.

Western modernist writers and intellectuals engaged seriously with Gitanjali, particularly those interested in mysticism and non-European cultures. W.B. Yeats’s enthusiastic endorsement carried significant weight, while Ezra Pound, though later critical, initially praised Tagore’s work. The poems influenced the development of English-language free verse and prose poetry, demonstrating alternatives to traditional metrical verse. The work contributed to early 20th-century Western fascination with Eastern spirituality, a cultural current that would intensify throughout the century.

Within Bengali literature, Gitanjali represented both an apex of traditional devotional poetry and a bridge to modernist experimentation. Later Bengali poets both emulated and reacted against Tagore’s achievement, with some embracing his spiritual orientation and lyrical style while others rejected what they perceived as excessive mysticism or aestheticism. The collection’s formal innovations—particularly Tagore’s development of modern literary Bengali—profoundly influenced subsequent Bengali poetry and prose.

Numerous adaptations and interpretations of Gitanjali have appeared across various media. Musicians worldwide have set Tagore’s verses to music, while choreographers have created dance performances inspired by the poems. Visual artists have produced illustrated editions, and the poems have been adapted for theater and film. In Bengal, Tagore’s own musical settings of many poems (as Rabindrasangeet) remain extraordinarily popular, performed regularly in concerts and domestic settings.

The work’s translation history reveals both its global appeal and the challenges of cross-cultural literary transmission. Gitanjali has been translated into virtually every major world language, with varying degrees of success. Each translation must negotiate between literal accuracy and poetic effect, between cultural specificity and universal accessibility. Some translators have returned to Tagore’s Bengali originals rather than working from his English versions, producing quite different results that sometimes diverge significantly from the Nobel Prize-winning text.

Physical Description and Editions

The original Bengali Gitanjali, published by the Indian Publishing House in Calcutta on August 4, 1910, comprised 157 poems across 104 pages. The first edition featured relatively simple typography and binding typical of Bengali literary publications of the period, making it accessible to middle-class readers rather than positioning it as a luxury item. This democratic approach to publication reflected Tagore’s commitment to reaching broad audiences rather than limiting his work to elite collectors.

The first English edition, published by the India Society in London in September 1912, was a limited edition of 750 copies, featuring an introduction by W.B. Yeats. This edition served primarily to introduce Tagore to British literary circles and was not widely commercially available. The subsequent Macmillan edition of March 1913, which would become the standard text, made the work broadly accessible to English-speaking readers worldwide. This edition maintained the simple elegance of the India Society version while ensuring widespread distribution through Macmillan’s established networks.

Subsequent editions have varied considerably in presentation. Some feature elaborate illustrations, including editions with artwork by Indian artists attempting to capture the poems’ spiritual essence visually. Others present minimalist text-focused designs emphasizing the poems’ meditative qualities. Scholarly editions include extensive annotation explaining cultural references and discussing translation issues, while popular editions focus on accessibility and aesthetic appeal.

Various institutions preserve important materials related to Gitanjali’s creation and publication. Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, the institution Tagore founded, maintains the most comprehensive collection of manuscripts, correspondence, and early editions. The British Library holds significant materials from the work’s English publication, including correspondence between Tagore, Rothenstein, and Yeats. These archival materials provide invaluable insights into the work’s composition, translation, and reception.

The physical artifacts associated with Gitanjali—manuscripts, correspondence, early editions—have achieved considerable cultural and monetary value. First editions, particularly of the India Society limited edition with Yeats’s introduction, command high prices among collectors. Tagore’s manuscript pages, when they appear at auction, attract intense interest from institutions and private collectors alike. This commercial valuation reflects the work’s canonical status and continuing cultural significance.

Scholarly Reception

Academic responses to Gitanjali have evolved considerably since its initial publication, reflecting changing critical methodologies and cultural contexts. Early Western critics, influenced by Yeats’s introduction and orientalist assumptions, often emphasized the work’s “mystical Eastern wisdom” and spiritual content while overlooking its literary sophistication and engagement with modernity. This romanticized reception sometimes reduced Tagore to a sage-like figure rather than recognizing him as a complex modern intellectual navigating multiple cultural influences.

Post-colonial scholarship has productively complicated these early readings, examining how Gitanjali negotiated between Indian and Western literary traditions, how Tagore’s self-translation involved significant creative adaptation rather than simple linguistic transfer, and how the work’s reception reflected power dynamics of colonialism and orientalism. Critics have noted how the English Gitanjali strategically emphasized certain aspects of Tagore’s poetry while downplaying others—particularly his engagement with contemporary social and political issues—to conform to Western expectations of Indian spirituality.

Comparative literature scholars have examined Gitanjali alongside other mystical poetry traditions, including Sufi verse, Christian mystical poetry, and secular modernist explorations of transcendence. These studies reveal both universal patterns in mystical discourse and culturally specific elements reflecting Tagore’s particular philosophical and religious background. The work emerges from such comparisons as simultaneously grounded in specific Indian traditions and participating in global conversations about spirituality, modernity, and poetic expression.

Translation studies scholars have given particular attention to Tagore’s self-translation, using Gitanjali as a case study in how poets adapt their work for different linguistic and cultural contexts. Research has revealed that the English versions often differ substantially from the Bengali originals in tone, imagery, and even meaning, raising questions about which version should be considered authoritative and how we should understand the relationship between translation and original creation.

Contemporary Indian critics have sometimes questioned Gitanjali’s canonical status, arguing that its selection for the Nobel Prize reflected Western preferences for spiritual themes over Tagore’s more politically engaged work, and that its continuing dominance overshadows other important Indian literary achievements. These debates reflect broader discussions about canonization, cultural representation, and the politics of recognition in postcolonial contexts.

Modern Relevance and Contemporary Perspectives

More than a century after its publication, Gitanjali continues to resonate with contemporary readers, though often in ways different from its initial reception. In an era of increasing secularization, environmental crisis, and digital disconnection, readers find in Tagore’s poems a model of spiritual seeking that transcends dogmatic religion while offering alternatives to purely materialistic worldviews. The work’s emphasis on finding the divine in nature and human relationships speaks to contemporary concerns about ecological consciousness and authentic human connection.

The poems’ exploration of creativity as spiritual practice has influenced contemporary discussions of contemplative arts and mindfulness practices. Writers, artists, and musicians draw on Gitanjali as inspiration for approaching creative work as a form of meditation and spiritual development rather than mere commercial production or self-expression. This dimension has gained particular relevance as artists seek alternatives to market-driven creative economies.

Educational institutions worldwide continue to teach Gitanjali, though pedagogical approaches have evolved. Rather than presenting it primarily as exotic spiritual wisdom from the East, contemporary educators tend to situate the work within its historical and cultural contexts while exploring its aesthetic innovations and cross-cultural negotiations. Students examine issues of translation, colonialism, and cultural exchange through the work, using it to consider broader questions about how literature travels across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

The work maintains particular significance within South Asian diaspora communities, serving as a cultural touchstone connecting generations to Bengali and broader Indian cultural heritage. Second- and third-generation immigrants often encounter Gitanjali as an accessible entry point to their ancestral culture, while the poems’ themes of longing and separation acquire additional resonance when read through the experience of diaspora and displacement.

Digital technologies have created new possibilities for engaging with Gitanjali. Online platforms host audio recordings of poems in multiple languages, video performances, and interactive editions with commentary and cultural context. Social media regularly features excerpts from the work, introducing it to audiences who might not otherwise encounter poetry. These digital disseminations raise questions about attention, context, and meaning in an age of algorithmic content delivery and shortened attention spans.

Environmental movements in India and globally have found inspiration in Gitanjali’s nature imagery and pantheistic vision. Activists cite Tagore’s reverence for natural beauty and his understanding of humanity’s interconnection with the natural world as precedents for contemporary ecological consciousness. The poems provide spiritual and philosophical resources for articulating environmental values rooted in Indian traditions rather than imported from Western environmental movements.

Conclusion

Gitanjali stands as a landmark achievement in world literature, a work that successfully bridged cultural divides while remaining grounded in specific Indian spiritual and literary traditions. Rabindranath Tagore’s collection of devotional poems transformed Indian literature’s global standing, demonstrated the translatability of profound spiritual experiences, and influenced both Eastern and Western literary developments throughout the 20th century and beyond.

The work’s significance extends beyond its immediate literary merits, important as those are. Gitanjali represents a crucial moment in cross-cultural understanding, when Eastern philosophical and spiritual perspectives gained serious attention in Western intellectual discourse. Tagore’s Nobel Prize challenged European cultural hegemony and validated non-European literary traditions at a critical historical moment. For Indians struggling under colonial rule, this recognition provided immense cultural capital and psychological affirmation.

Yet Gitanjali’s ultimate value lies not in its historical importance but in its continuing capacity to move readers across cultures and generations. The poems’ exploration of spiritual longing, divine presence, creative expression, and human mortality addresses perennial concerns that transcend specific historical circumstances. Tagore’s achievement was to express these universal themes through imagery and metaphors rooted in Bengali cultural experience while rendering them accessible to readers from radically different backgrounds.

The work reminds contemporary readers that poetry can address fundamental spiritual questions without succumbing to dogmatism or sentimentality, that cultural specificity and universal accessibility need not be opposed, and that literature can contribute to cross-cultural understanding while maintaining artistic integrity. As the world becomes simultaneously more connected and more fragmented, Gitanjali’s model of rooted cosmopolitanism—deeply grounded in particular traditions while open to global dialogue—offers valuable lessons.

Gitanjali ultimately celebrates the human capacity for transcendence through art, devotion, and connection with others and the natural world. Its enduring appeal testifies to humanity’s continuing hunger for spiritual meaning and aesthetic beauty, needs that literature uniquely satisfies. As long as readers seek poetry that speaks to both mind and spirit, that balances tradition with innovation, and that finds the universal in the particular, Gitanjali will continue to find audiences and inspire new generations of readers, writers, and seekers.

Sources:

- Wikipedia article on Gitanjali

- Wikidata structured information (Q2358930)

- Historical publication data from Wikipedia infobox

- Images from Wikimedia Commons under various Creative Commons and Public Domain licenses

Note: This content is based on available source materials. Specific details about individual poems, detailed translation comparisons, and comprehensive scholarly reception would require additional primary and secondary sources beyond those provided.