Meghadūta

Ancient Sanskrit lyric poem by Kālidāsa about a banished yakṣa's message of love carried by a cloud, influencing centuries of Indian literature.

Gallery

Gallery

The Banished Yaksha - a painting by Abanindranath Tagore inspired by Meghadūta

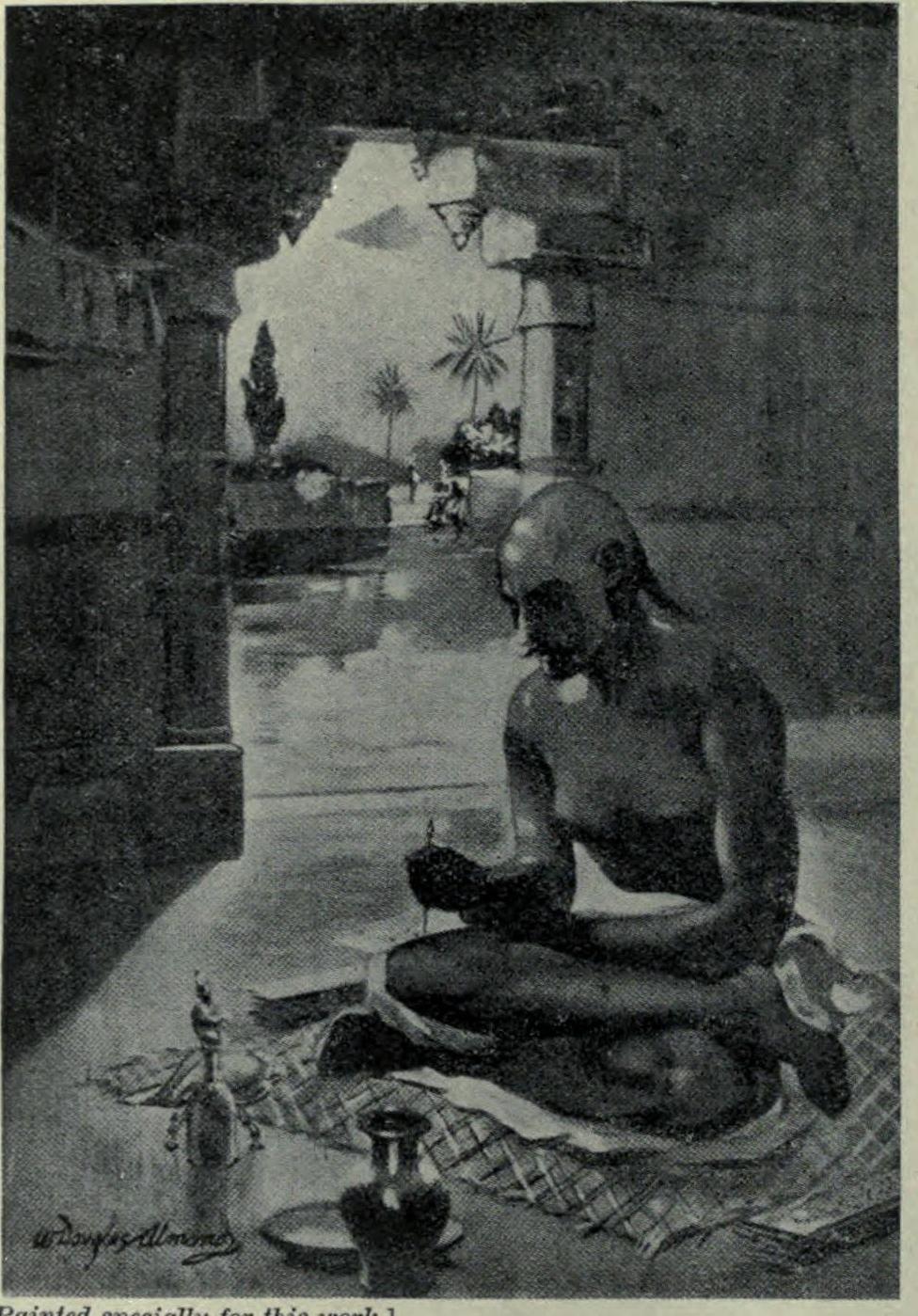

Kālidāsa composing the Meghadūta, imagined by William Douglas Almond

Indian postage stamp from 1960 commemorating Meghadūta

Visualization of the yakṣa's dwelling as described in Meghadūta

Introduction

In the annals of world literature, few poems capture the essence of separation, longing, and the transformative power of nature quite like Meghadūta (literally “Cloud Messenger”). Composed by the immortal Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa, this lyric masterpiece stands as one of the most beloved works in the classical Indian literary canon. The poem’s elegant simplicity—a banished yakṣa (celestial being) entreating a monsoon cloud to carry messages to his beloved wife—belies its profound emotional depth and sophisticated artistry.

Written in the mandākrāntā meter, Meghadūta represents the pinnacle of Sanskrit lyric poetry and exemplifies Kālidāsa’s unparalleled mastery over language, imagery, and emotion. The work is generally dated to the 4th-5th century CE, during the flourishing Gupta period, often considered the golden age of Sanskrit literature and arts. Through approximately 120 verses divided into two parts—Pūrvamegha (First Cloud) and Uttaramegha (Latter Cloud)—Kālidāsa weaves together themes of love, separation, nature’s beauty, and geographical description into a seamless tapestry of poetic excellence.

The influence of Meghadūta on subsequent Indian literature cannot be overstated. It established an entirely new genre known as sandeśakāvya or messenger poetry, inspiring countless poets across languages and centuries to compose similar works. The poem became particularly influential in Bengali literature, where it sparked a rich tradition of imitative and adaptive works, demonstrating its enduring appeal across regional and temporal boundaries.

Historical Context

The Gupta Golden Age

Meghadūta was composed during the Gupta Empire period (circa 320-550 CE), an era that witnessed unprecedented cultural, artistic, and intellectual achievements in ancient India. This period is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of Indian civilization, marked by remarkable advances in literature, art, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy. The Gupta rulers were great patrons of learning and arts, creating an environment where literary genius could flourish.

Sanskrit literature reached its zenith during this period, with poets and playwrights enjoying royal patronage and popular acclaim. The courts of Gupta emperors, particularly those of Chandragupta II Vikramāditya, were gathering places for scholars, poets, and artists. It is within this milieu that Kālidāsa, regarded as one of the “nine gems” (navaratna) of Vikramāditya’s court according to tradition, created his timeless works.

Literary Traditions and Innovation

While drawing upon established Sanskrit poetic conventions and earlier literary traditions, Meghadūta represents a striking innovation in form and content. Prior to Kālidāsa, Sanskrit poetry primarily consisted of mahākāvyas (epic poems) focusing on heroic narratives, and shorter lyric poems. Meghadūta introduced the sandeśakāvya or messenger poem genre, where the primary narrative device involves a message being conveyed through an intermediary—in this case, a cloud.

The choice of a cloud as messenger demonstrates Kālidāsa’s deep understanding of Indian cultural consciousness. In the Indian subcontinent, monsoon clouds are not merely meteorological phenomena but bearers of life, renewal, and emotional symbolism. The arrival of monsoon rains after the scorching summer has always been celebrated in Indian culture, associated with fertility, abundance, and the reunion of lovers.

Creation and Authorship

Kālidāsa: The Master Poet

While much about Kālidāsa’s life remains shrouded in uncertainty, his literary legacy is indisputable. Regarded as the greatest Sanskrit poet and dramatist, Kālidāsa’s works include several mahākāvyas (Raghuvaṃśa and Kumārasambhava), plays (Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Vikramorvaśīyam, and Mālavikāgnimitram), and the lyric poems Meghadūta and Ṛtusaṃhāra.

The exact dates of Kālidāsa’s life are debated among scholars, with estimates ranging from the 4th to 5th century CE. Traditional accounts associate him with the court of King Vikramāditya, though historical verification remains elusive. What is certain is that Kālidāsa possessed an extraordinary command over Sanskrit language, an intimate knowledge of Indian geography, flora, and fauna, and a profound understanding of human emotions.

Artistic Inspiration and Composition

The inspiration behind Meghadūta remains a subject of scholarly speculation. Some traditions suggest that Kālidāsa himself experienced separation from a loved one, channeling personal emotion into poetic expression. Others view it as a purely artistic creation, demonstrating the poet’s imaginative genius and technical virtuosity.

The poem’s setting—beginning at Rāmagiri (modern-day Ramtek in Maharashtra)—provides the geographical anchor for the yakṣa’s message. From this remote mountain where the celestial being serves his one-year exile, the poem traces an elaborate route across ancient India, describing cities, rivers, mountains, and sacred sites with remarkable topographical accuracy and poetic embellishment.

Content and Themes

Synopsis

Meghadūta opens with a yakṣa, a celestial attendant of Kubera (the god of wealth), suffering in exile at Rāmagiri for neglecting his duties. As the monsoon season approaches—marked by the arrival of the first cloud—the yakṣa is overwhelmed by memories of his beloved wife, left behind in Alakā, Kubera’s mythical capital in the Himalayas.

Unable to bear the separation and with four months remaining until his return, the yakṣa addresses a passing cloud, requesting it to carry messages to his wife. In the Pūrvamegha (verses 1-65), he describes the detailed route the cloud should follow, passing through various kingdoms, cities, mountains, and rivers of ancient India. His descriptions serve multiple purposes: providing directions to the cloud, revealing his intimate knowledge of the landscape, and expressing his longing through associations with each location.

In the Uttaramegha (verses 66-120), the yakṣa describes Alakā and his home in vivid detail, then provides the specific messages the cloud should convey to his wife. He imagines her state—pining in separation, observing religious vows for his return, growing thin with grief. The messages alternate between reassurance and shared longing, culminating in a poignant expression of hope for their reunion.

Major Themes

Separation and Longing (vipralambha śṛṅgāra): The poem is fundamentally an exploration of vipralambha śṛṅgāra—the aesthetic sentiment of love in separation. Kālidāsa masterfully depicts the psychological state of lovers separated by circumstances beyond their control, capturing universal emotions through particular circumstances.

Nature as Mirror and Messenger: Nature in Meghadūta is not merely backdrop but active participant. The cloud becomes both messenger and sympathetic companion, while rivers, mountains, forests, and cities serve as repositories of memories and emotional associations. Kālidāsa’s detailed natural descriptions demonstrate his profound observation and ability to invest landscape with emotional meaning.

Geography and Cultural Identity: The poem’s geographical journey from central India to the Himalayas functions as a celebration of the Indian subcontinent’s diversity and beauty. Each location mentioned carries cultural and mythological significance, creating a poetic map that interweaves physical geography with cultural memory.

The Monsoon as Life Force: The arrival of monsoon clouds represents renewal, fertility, and hope. For the separated lover, the monsoon intensifies longing but also brings the promise of reunion. Kālidāsa’s descriptions of monsoon phenomena—clouds gathering, lightning flashing, peacocks dancing, rivers swelling—create a sensuous backdrop for the emotional narrative.

Devotion and Duty: The yakṣa’s exile results from neglecting duty, yet his love and faithfulness during separation become forms of devotion. The poem explores the tension between worldly obligations and personal emotions, ultimately affirming the value of faithful love.

Artistic Analysis

Poetic Structure and Meter

Meghadūta is composed entirely in the mandākrāntā meter, characterized by its slow, stately movement (seventeen syllables per quarter-verse). This meter choice is particularly appropriate for the poem’s contemplative mood and elaborate descriptions. The mandākrāntā’s graceful rhythm mirrors the measured progress of clouds across the sky, while allowing for complex syntactic structures and extended imagery.

The poem’s division into Pūrvamegha and Uttaramegha creates a clear structural progression—from journey to destination, from external landscape to intimate domestic space, from geographical description to emotional address. This bipartite structure balances descriptive and emotive elements while maintaining narrative momentum.

Imagery and Symbolism

Kālidāsa’s imagery in Meghadūta demonstrates his unparalleled descriptive powers. His cloud is anthropomorphized yet maintains its elemental nature—it can understand the yakṣa’s plea, travel specific routes, and deliver messages, yet it remains composed of water, moves with wind, and manifests through lightning and rain.

The upamā (simile) and rūpaka (metaphor) employed throughout showcase Kālidāsa’s technical mastery. Mountains are compared to elephants, rivers to women in various moods, lightning to a golden line on a sapphire plate. These comparisons are not merely decorative but reveal deeper connections between natural and human realms.

Water imagery pervades the poem—rivers, clouds, rain, tears—suggesting the fluidity of emotions and the life-giving nature of connection. The contrast between the dry summer season (associated with separation) and the wet monsoon (associated with hoped-for reunion) structures the emotional arc.

Literary Devices

Kālidāsa employs the full range of Sanskrit poetic devices (alaṃkāra) with remarkable subtlety. Upamā (simile), rūpaka (metaphor), utprekṣā (poetic fancy), atiśayokti (hyperbole), and dīpaka (enlightener) appear throughout, never overshadowing emotional truth but enhancing poetic effect.

The poem’s dhvani (suggestive meaning) operates on multiple levels. Surface descriptions of locations carry emotional associations; messages to the wife suggest unspoken depths of feeling; the cloud itself symbolizes both separation (as it can travel where the yakṣa cannot) and connection (as carrier of messages).

Cultural Significance

Place in Sanskrit Literary Canon

Meghadūta occupies a unique position in Sanskrit literature. While shorter than Kālidāsa’s mahākāvyas, it is considered his most perfect work—a poem where every verse contributes to the whole, maintaining emotional intensity throughout while displaying technical virtuosity. Sanskrit literary critics have praised it as alaṃkārabhūṣitaṃ kāvyam—poetry adorned with figures of speech—where form and content achieve ideal unity.

The poem became a standard text for Sanskrit education, with numerous commentaries written to explicate its meaning, poetic devices, and cultural references. Major commentators include Vallabhadeva (10th century), Mallinatha (14th century), and numerous others, demonstrating the work’s enduring centrality to Sanskrit literary studies.

Religious and Philosophical Dimensions

While not explicitly religious, Meghadūta contains numerous references to Hindu deities, sacred sites, and religious practices. The yakṣa’s devotion to his wife parallels devotional relationships with the divine, while his separation-induced suffering evokes viraha (spiritual longing for the divine) found in bhakti literature.

The poem’s geography traces a sacred map of India, mentioning Ujjain, Vidisha, Dasapura, and numerous temples and pilgrimage sites. The descriptions often emphasize religious activities—temple worship, religious vows, sacred bathing—integrating spiritual practice into everyday life.

The yakṣa’s exile for neglecting duty raises questions about dharma (righteous action) and the consequences of lapses. His faithful love during separation becomes a form of tapas (austerity), suggesting that emotional fidelity itself is spiritually meaningful.

Influence and Legacy

The Sandeśakāvya Tradition

Meghadūta’s most significant literary legacy is establishing the sandeśakāvya or messenger poem genre. This genre involves a separated lover sending messages through natural phenomena (clouds, birds, wind) or other messengers, describing routes and conveying emotions. The tradition flourished across India, with notable examples including:

- Pavanadūta (Wind Messenger) by Dhoyi

- Haṃsadūta (Swan Messenger) by Rūpa Gosvāmī

- Mayūradūta (Peacock Messenger) attributed to Udayanācārya

- Śukasandeśa (Parrot Messenger) by Rūpagosvāmī

- Bhramaradūta (Bee Messenger) by various poets

Most significantly for the available sources, Korada Ramachandra Sastri composed Ghanavrttam as a sequel to Meghadūta, continuing the yakṣa’s story and demonstrating the work’s continued inspiration to poets centuries after composition.

Influence on Regional Literatures

Meghadūta became extraordinarily influential in Bengali literature, inspiring numerous poets to create similar messenger poems in Bengali. The work was translated and adapted repeatedly, with Bengali poets drawing on its themes, structure, and imagery while adapting them to local contexts and languages.

Beyond Bengali, the poem influenced literary traditions in Hindi, Marathi, Kannada, Telugu, and other Indian languages. Each tradition adapted the messenger poem convention while maintaining the core emotional themes and narrative structure established by Kālidāsa.

Modern Adaptations and Interpretations

In the modern era, Meghadūta has been translated into numerous world languages, introducing global audiences to Sanskrit poetry’s refinement. Notable English translations include those by H.H. Wilson (1813), one of the earliest, and numerous subsequent versions by scholars and poets attempting to capture Kālidāsa’s artistry in English.

The poem has inspired visual artists, including the renowned Bengali painter Abanindranath Tagore, whose painting “The Banished Yaksha” depicts the poem’s protagonist. The Government of India issued a commemorative postage stamp in 1960 featuring the yakṣa pleading with the cloud, demonstrating the work’s status as national cultural heritage.

Contemporary poets, scholars, and artists continue to find inspiration in Meghadūta, creating new interpretations, performances, and artistic responses. The poem’s themes of separation, longing, and the power of communication resonate with modern experiences of distance and connection.

Scholarly Reception

Traditional Commentary Tradition

Sanskrit literary scholarship developed an extensive commentary tradition around Meghadūta, with scholars analyzing its language, poetic devices, geographical references, and cultural allusions. The major commentaries include:

Vallabhadeva’s commentary (10th century) provides detailed explanations of verses, identifying poetic figures and clarifying geographical and cultural references. His work established standards for subsequent commentators.

Mallinatha’s commentary (14th century) became particularly influential, often published alongside the text in modern editions. Mallinatha’s explanations balance linguistic analysis with literary appreciation, making the poem accessible while highlighting its sophistication.

Later commentaries continued this tradition, with scholars from various regions contributing interpretations reflecting their own cultural contexts while honoring the text’s classical status.

Modern Academic Scholarship

Modern scholarship approaches Meghadūta from multiple perspectives. Literary critics analyze its structure, imagery, and place in Sanskrit poetic tradition. Linguists study its language and meter as exemplifying classical Sanskrit’s possibilities. Geographers and historians use its detailed route descriptions to understand ancient Indian topography and urban development.

Cultural studies scholars examine how the poem constructs Indian geographical and cultural identity, noting how Kālidāsa’s poetic journey creates a unified vision of diverse regions. Feminist scholars have offered readings of the yakṣa’s wife as both idealized figure and individual with her own emotional reality.

Comparative literature approaches situate Meghadūta within world poetry traditions, noting parallels with other separation poems while highlighting its distinctive features. The messenger poem convention itself has been compared to similar devices in other literary traditions.

Debates and Interpretations

Scholarly debates continue regarding various aspects of Meghadūta. The exact route described by the yakṣa has been subject to geographical analysis and debate, with scholars attempting to identify all mentioned locations precisely. Some descriptions resist definitive identification, leaving room for interpretive differences.

The poem’s relationship to real geography versus poetic imagination remains discussable. While many locations are clearly identifiable, others may represent idealized or composite descriptions. This ambiguity between documentary accuracy and poetic license reflects classical Sanskrit poetics’ broader tensions between reality and imagination.

The yakṣa’s wife remains somewhat enigmatic—described through her husband’s imagination and the cloud’s potential observations rather than given direct voice. Interpretations vary regarding whether this represents patriarchal limitation or sophisticated psychological portraiture of longing that projects onto the absent beloved.

Geographic and Topographic Significance

The Poetic Journey

Meghadūta’s geographic descriptions trace a specific route from Rāmagiri (Ramtek in Maharashtra) northward through central India to the Himalayas. The journey passes through:

- Vidisha (modern Besnagar in Madhya Pradesh)

- Ujjayinī (Ujjain, ancient Avanti’s capital)

- Dasapura (Mandsaur)

- Devagiri (possibly in the Aravallis)

- The Nīlā River (possibly the Nīlarudra or Nerbudda’s tributary)

- Kurukṣetra (the sacred plain)

- The Himalayan foothills and peaks

- Alakā (Kubera’s mythical capital)

Each location is described with attention to distinctive features—rivers, temples, gardens, mountains—creating both navigational directions and emotional associations. The yakṣa’s knowledge of these places suggests his own travels and memories, adding personal dimension to geographical description.

Cultural Landscape

Beyond physical geography, Kālidāsa describes a cultural landscape of sacred sites, royal cities, agricultural abundance, and natural beauty. His descriptions emphasize human harmonious relationship with nature—city gardens, temple tanks, riverbank gatherings—presenting an idealized vision of settled, cultured life.

The sacred geography is particularly significant. References to temples, religious practices, and mythologically significant locations integrate spiritual meaning into physical space. The journey becomes a pilgrimage of sorts, moving through sanctified landscape toward reunion.

Conclusion

Meghadūta stands as a supreme achievement of Sanskrit lyric poetry and a testament to Kālidāsa’s genius. Through approximately 120 verses, it captures universal emotions of love and separation while celebrating the Indian subcontinent’s geographical and cultural richness. The poem’s influence extended far beyond its historical moment, establishing a literary genre, inspiring countless adaptations, and continuing to move readers across languages and centuries.

The work’s enduring appeal lies in its perfect balance of technical sophistication and emotional authenticity. Kālidāsa’s elaborate poetic devices never obscure the yakṣa’s genuine suffering and hope; his detailed geographical descriptions never become mere catalog but remain emotionally charged with longing and memory.

For students of Indian literature and culture, Meghadūta offers insight into classical aesthetic values, poetic conventions, religious practice, geographical knowledge, and emotional life of the Gupta period. For general readers, it provides a moving meditation on separation, communication, and the power of imagination to bridge distance.

As monsoon clouds continue to darken Indian skies each year, Meghadūta remains relevant—a reminder that while human circumstances change, fundamental emotions of love, loss, longing, and hope persist. The yakṣa’s plea to the cloud speaks across fifteen centuries, demonstrating poetry’s unique ability to preserve and communicate human experience in all its intensity and beauty.