Natya Shastra

Ancient Sanskrit treatise on performing arts by sage Bharata, foundational text for Indian classical dance, drama, and music traditions.

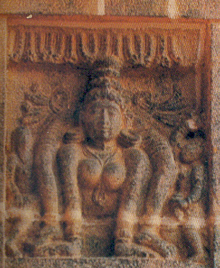

Gallery

Gallery

Shiva as Nataraja embodies the cosmic dance principles described in Natya Shastra

Mani Madhava Chakyar demonstrating Sringara, one of the nine rasas defined in Natya Shastra

Bharatanatyam dance derives its theoretical foundation from Natya Shastra

Theatrical portrayal of Ravana following Natya Shastra conventions

Kuncitam, one of the karanas (dance units) codified in Natya Shastra

The Natya Shastra stands as one of the most comprehensive and influential treatises on the performing arts ever composed in human history. Attributed to the sage Bharata Muni, this monumental Sanskrit text encompasses the complete theory and practice of drama, dance, music, and aesthetics that has shaped Indian cultural expression for over two millennia. More than a technical manual, the Natya Shastra is a philosophical exploration of how art transforms human consciousness, introducing concepts like rasa (aesthetic essence) and bhava (emotion) that continue to resonate in performance traditions across South and Southeast Asia.

The text’s compilation is generally dated between 200 BCE and 200 CE, though scholarly estimates range more broadly from 500 BCE to 500 CE, reflecting the challenges of dating ancient Sanskrit works that were transmitted orally before being committed to writing. Despite this chronological uncertainty, the Natya Shastra’s influence on Indian civilization is unquestionable—it forms the theoretical foundation for all major Indian classical dance forms, provides the framework for Sanskrit drama, and establishes aesthetic principles that permeate Indian artistic thought.

What makes the Natya Shastra particularly remarkable is its systematic and encyclopedic approach. Comprising approximately 6,000 verses organized into 36 or 37 chapters (depending on the recension), the treatise covers everything from theater architecture and stage design to the minute details of hand gestures, eye movements, and footwork. It discusses makeup, costumes, dramatic genres, audience psychology, and the training of performers with equal rigor, creating a complete science of performance that has rarely been matched in its comprehensiveness.

Historical Context

The Natya Shastra emerged during a pivotal period in Indian intellectual history, when systematic treatises (shastras) were being composed across various domains of knowledge—from grammar and logic to statecraft and architecture. This was an era when oral traditions were being codified into written texts, when the great epics were achieving their final forms, and when philosophical systems were being systematically articulated. The compilation of the Natya Shastra represents part of this broader movement to preserve and systematize traditional knowledge.

The text itself claims divine origins, beginning with a mythological narrative about how the gods requested Brahma to create a fifth Veda that would be accessible to all social classes, unlike the four Vedas which had restrictions on who could study them. Brahma responded by creating Natya Veda (the Veda of drama), drawing the text (pathya) from the Rigveda, music (gita) from the Samaveda, gesture (abhinaya) from the Yajurveda, and emotional experience (rasa) from the Atharvaveda. He then taught this knowledge to sage Bharata, who transmitted it to his hundred sons and codified it in the Natya Shastra.

This mythological framing is significant beyond its religious dimensions—it positions the performing arts as having the same sacred status as the Vedas while making them accessible to all, regardless of caste or gender. This democratic impulse reflects the social function of theater in ancient India, where performances served as a medium for transmitting cultural values, religious narratives, and social norms to diverse audiences.

The period of the text’s composition coincided with the flourishing of Sanskrit drama, which would reach its peak in the classical period with playwrights like Kalidasa, Bhasa, and Shudraka. The Natya Shastra provided the theoretical framework within which these dramatists worked, establishing conventions that shaped their creative choices. The text emerged in a cultural environment where patronage for the arts was strong, where urban centers supported permanent theater companies, and where sophisticated audiences appreciated the nuances of dramatic performance.

Structure and Content

The Natya Shastra is organized into chapters (adhyayas) that systematically address different aspects of the performing arts. While the exact number and arrangement of chapters vary across manuscript traditions, the major divisions cover the following areas:

Origins and Purpose of Drama: The opening chapters present the mythological origin of theater and discuss its purpose—to provide instruction and entertainment (lokayatra), to console the afflicted, and to perpetuate dharma (righteous conduct). Drama is presented as a mirror to life, reflecting all aspects of human experience.

Theater Architecture: Several chapters provide detailed specifications for constructing performance spaces, including measurements, proportions, and ritual consecration. The text describes three types of playhouses (rectangular, square, and triangular) sized for different audience capacities, with specific requirements for the stage area, green room, and audience seating.

Preliminary Rituals: Before performances, the text prescribes elaborate consecration rituals (pūrvaranga) involving offerings to various deities, guardian spirits, and theatrical traditions. These rituals establish the sacred nature of the performance space and invoke divine protection.

Rasa Theory: Perhaps the most influential section philosophically, Chapters 6-7 elaborate the theory of rasa—the aesthetic experience or emotional essence that arises in the audience through artistic representation. The text identifies eight primary rasas: shringara (romantic love), hasya (humor), karuna (pathos), raudra (fury), vira (heroism), bhayanaka (terror), bibhatsa (disgust), and adbhuta (wonder). Later traditions added shanta (peace) as a ninth rasa. Each rasa emerges from the artistic portrayal of specific determinants (vibhava), consequents (anubhava), and transitory emotions (vyabhichari bhava).

Bhava: Complementing the rasa theory, the text identifies 49 bhavas or emotional states—8 stable emotions (sthayibhava) that correspond to the eight rasas, 33 transitory emotions, and 8 involuntary physical responses (sattvikabhavas) like tears, trembling, and changes in voice or complexion.

Abhinaya (Acting): Four types of acting are distinguished: angika (bodily movements), vachika (verbal expression including speech, song, and intonation), aharya (costume, makeup, and decoration), and sattvika (psychological representation of emotion). Detailed chapters explain each type with remarkable precision.

Body Movements: The text catalogues 108 karanas—fundamental units of dance combining hand gestures (hastas), foot positions, and body postures. It describes movements of the head (shirobheda), eyebrows, nose, cheeks, lower lip, chin, neck, chest, sides, thighs, shanks, and feet. The classification of 13 head positions, 7 eye movements, 36 glances, and 24 single-hand gestures (asamyukta hasta) and 13 combined-hand gestures (samyukta hasta) demonstrates the text’s systematic approach.

Musical Theory: Several chapters address music (sangita), including scales (gramas), notes (svaras), intervals (shrutis), rhythm (tala), instruments, and melodic modes (jatis). The Natya Shastra’s music theory influenced the development of both Hindustani and Carnatic classical music traditions.

Language and Metrics: The text discusses the appropriate use of Sanskrit and Prakrit languages for different character types, poetic meters suitable for various dramatic situations, and prosodic principles.

Dramatic Genres: The Natya Shastra classifies plays into two major categories—rupaka (major dramatic forms) and uparupaka (minor dramatic forms)—with subdivisions based on plot structure, character types, and thematic content. Ten types of major plays are identified, including the nataka (heroic play), prakarana (social play), and bhana (monologue).

Character Types: The text categorizes dramatic characters into types (svabhava) based on psychological temperament, social status, age, and gender, providing actors with guidelines for portraying each type convincingly.

Production Elements: Later chapters address practical aspects including makeup, costumes, stage properties, success factors for performances, and even the qualities required in performers, musicians, and stage managers.

The Rasa Theory: A Revolutionary Aesthetic

The Natya Shastra’s most profound contribution to world aesthetics is its rasa theory, which offers a sophisticated explanation of how art creates aesthetic experience. The term rasa literally means “juice,” “essence,” or “flavor,” and the theory proposes that art distills essential emotional experiences that audiences can savor much as one tastes flavors in food.

According to Bharata’s formulation, rasa is not the mere representation of an emotion on stage, nor is it simply the emotion felt by the audience member. Rather, it emerges through a transformative process where the portrayed emotions (bhavas), their causes and contexts (vibhavas), their physical manifestations (anubhavas), and accompanying transitory feelings (vyabhichari bhavas) combine to create a universalized aesthetic experience that transcends personal emotion.

The famous rasa sutra (aphorism on aesthetic essence) states:

vibhāvānubhāva-vyabhicāri-samyogād rasa-niṣpattiḥ

“Rasa is produced from the combination of determinants, consequents, and transitory emotions.”

This seemingly simple formula contains profound implications. The spectator does not experience rasa by identifying personally with the character’s emotion but through a contemplative aesthetic distance that allows appreciation of the emotion’s essential quality. This “aesthetic distance” concept predates similar ideas in Western aesthetics by over a millennium.

The eighth primary rasa, adbhuta (wonder or marvel), is particularly significant in the Natya Shastra’s scheme. Unlike the other rasas that correspond to recognizable emotions, adbhuta represents the sense of awe and transcendent marvel that art itself can produce—a meta-aesthetic experience that elevates the spectator beyond ordinary emotional states.

Later philosophers, particularly Abhinavagupta in his Abhinavabharati commentary (10th-11th century CE), further developed rasa theory, proposing shanta (tranquility) as a ninth rasa and exploring the metaphysical dimensions of aesthetic experience. Abhinavagupta argued that rasa experience provides a glimpse of the bliss (ananda) of pure consciousness, making art a spiritual practice.

Dance and Physical Expression

The Natya Shastra’s treatment of dance (nritta and nritya) established principles that continue to govern Indian classical dance traditions. The text makes important distinctions between pure dance (nritta)—rhythmic movements performed for their own aesthetic sake—and expressive dance (nritya)—movements that convey meaning and emotion.

The 108 karanas described in the text form the basic vocabulary of classical Indian dance. Each karana is a precisely defined combination of foot position, leg stance, body posture, and hand gesture that can be photographed as a single moment in the dance sequence. These karanas are not isolated movements but flow into one another, creating angaharas (longer movement phrases) and ultimately complete dance sequences.

The text’s codification of hand gestures (hastas or mudras) is particularly influential. The 24 single-hand gestures and 13 combined-hand gestures described can represent objects, actions, emotions, relationships, and abstract concepts. For example, the pataka hasta (flag hand) with fingers extended together can represent a cloud, riverbank, knife, or the concept of “now,” depending on context. This symbolic language allows dancers to “narrate” complex stories purely through gesture.

Eye movements receive extraordinary attention in the Natya Shastra. The text describes how the eyes should move in coordination with other facial features and how different eye positions convey different meanings. The famous drishti bhedas (eye variations) include movements like looking straight ahead (sama), askance (alokita), sideways (sachi), with partially closed lids (milita), and others. Each has specific applications in expressing emotions and situations.

The sophistication of these descriptions suggests that by the time the Natya Shastra was compiled, a highly developed dance tradition already existed. The text was systematizing and recording knowledge that had been refined through generations of practice.

Musical Foundations

While the Natya Shastra is most famous for its dramatic and dance theory, its contributions to Indian musical theory are equally significant. The text describes an elaborate system of musical scales, rhythmic patterns, and instrumental practices that influenced the subsequent development of both North and South Indian classical music.

The Natya Shastra identifies 22 shrutis (microtones) within the octave—subtle pitch variations that create the characteristic sound of Indian music. These shrutis are organized into seven basic notes (svaras): shadja, rishabha, gandhara, madhyama, panchama, dhaivata, and nishada (roughly equivalent to sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni in sargam notation). The precise intonation of these notes and their relationships create different emotional colors.

The text describes two parent scales or gramas: shadja-grama and madhyama-grama, from which seven melodic modes (jatis) are derived. Each jati has specific characteristics including a predominant note (vadi), a secondary important note (samvadi), notes to be emphasized, and notes to be minimized. These jatis are ancestral to the later raga system that dominates Indian classical music.

Rhythm receives equally systematic treatment. The Natya Shastra describes various rhythmic cycles (talas) and tempo variations. The fundamental unit is the matra (beat), organized into rhythmic groupings with specific patterns of stressed and unstressed beats. The text identifies numerous talas suitable for different dramatic situations and musical compositions.

Four types of musical instruments are classified: stringed instruments (tata), wind instruments (sushira), percussion instruments (avanaddha), and solid/metallic instruments (ghana). Detailed descriptions of construction, tuning, and playing techniques are provided for various instruments including the vina (lute), venu (flute), mridanga (drum), and cymbals.

The integration of music with drama is carefully considered. The text prescribes which musical modes and rhythms are appropriate for different rasas, times of day, seasons, and dramatic situations. This integrated approach—where music, dance, and drama work together to create unified aesthetic experience—characterizes Indian performing arts traditions to this day.

Influence on Indian Classical Dance

Every major Indian classical dance form acknowledges the Natya Shastra as its foundational text. While each tradition has developed its own distinctive style, regional characteristics, and supplementary treatises, all trace their theoretical lineage to Bharata’s work.

Bharatanatyam, the classical dance of Tamil Nadu, explicitly structures its practice around Natya Shastra principles. The adavus (basic steps) of Bharatanatyam derive from the text’s karanas. The abhinaya (expressive) portions of Bharatanatyam directly apply the hand gestures, eye movements, and emotional expressions codified in the Natya Shastra. The organization of a Bharatanatyam recital—beginning with alarippu (pure dance), progressing through various compositions, and culminating in the expressive padam—reflects the text’s prescription for balanced performance.

Kathak, the classical dance of North India, similarly draws from the Natya Shastra while incorporating later influences from Mughal court culture. The nritta (pure dance) sections of Kathak with their complex rhythmic footwork exemplify the text’s principles of pure movement. The nritya (expressive) sections use the hand gestures described in the Natya Shastra to enact stories, often from Krishna’s life.

Kathakali, the dance-drama tradition of Kerala, perhaps most directly embodies the Natya Shastra’s comprehensive vision of theater. Kathakali integrates music, dance, acting, elaborate costume and makeup, and dramatic narrative in exactly the manner prescribed by Bharata. The mudras (hand gestures) in Kathakali follow the Natya Shastra’s system, though with some regional variations. The highly stylized facial expressions and eye movements that characterize Kathakali are refined applications of the text’s instructions.

Odissi from Odisha, Kuchipudi from Andhra Pradesh, Manipuri from Manipur, Mohiniyattam from Kerala, and Sattriya from Assam—all acknowledge the Natya Shastra as foundational while emphasizing different aspects of its teachings and incorporating regional characteristics.

The 20th-century revival of several classical dance forms explicitly invoked the Natya Shastra as authoritative tradition. When dance reformers like Rukmini Devi Arundale worked to establish Bharatanatyam as a respectable classical art, they emphasized its connection to the ancient Natya Shastra, lending the dance form cultural legitimacy. Similar processes occurred with other classical forms.

Sanskrit Drama and the Natya Shastra

The golden age of Sanskrit drama (roughly 1st-7th centuries CE) unfolded within the framework established by the Natya Shastra. While earlier dramas may have existed before the text’s compilation, the systematic codification influenced all subsequent dramatic composition.

Classical Sanskrit plays follow the conventions prescribed in the Natya Shastra: the use of both Sanskrit and Prakrit languages (Sanskrit for elevated characters, Prakrit for women and lower-status characters), the classification into specific dramatic genres (nataka, prakarana, etc.), the inclusion of prescribed preliminaries (purvaranga), and attention to rasa theory in dramatic construction.

Kalidasa’s masterpiece Abhijnanasakuntalam (The Recognition of Shakuntala) exemplifies these principles. The play follows the nataka (heroic drama) format prescribed in the Natya Shastra, with a royal hero, divine or semi-divine heroine, and a plot based on well-known legend. The language distribution follows convention, with King Dushyanta speaking Sanskrit while Shakuntala and her companions use Prakrit. The play’s famous scenes—the wooing in the hermitage, the curse and separation, the final recognition—are constructed to evoke specific rasas in succession: shringara (romance), karuna (pathos), adbhuta (wonder).

Bhasa, whose plays were rediscovered in the early 20th century, shows even earlier dramatic composition following Natya Shastra principles. His plays Swapnavasavadatta (Vasavadatta in a Dream) and Madhyamavyayoga (The Middle One) demonstrate sophisticated understanding of dramatic structure, character types, and rasa creation as outlined in the treatise.

The Natya Shastra’s influence extended beyond Sanskrit to regional dramatic traditions. The medieval devotional dramas (bhakti natya) of various regions, folk theater forms like jatra in Bengal and tamasha in Maharashtra, and even modern Indian theater bear traces of conventions established in the ancient text.

Transmission and Commentaries

The Natya Shastra exists in multiple manuscript traditions with variations in chapter organization and content. This textual fluidity reflects the oral transmission process and the practical nature of the text—performers and teachers presumably emphasized different aspects relevant to their traditions.

The most important commentary on the Natya Shastra is Abhinavagupta’s Abhinavabharati, composed in Kashmir around 1000 CE. This extensive commentary not only explicates obscure passages but significantly develops the philosophical dimensions of rasa theory. Abhinavagupta interprets aesthetic experience through the lens of Kashmir Shaivism, connecting theatrical rasa to the bliss of ultimate reality (brahmananda). His commentary became the standard interpretation for subsequent centuries and profoundly influenced Indian aesthetic philosophy.

Other medieval commentaries exist, though many are lost or fragmentary. Each regional performance tradition developed its own supplementary texts that applied Natya Shastra principles to specific contexts. For example, the Abhinaya Darpana (Mirror of Gesture) by Nandikesvara, probably from the 6th century, provides more detailed descriptions of hand gestures and body movements, becoming essential for classical dance. The Sangita Ratnakara by Sharngadeva (13th century) extensively develops the musical portions of the Natya Shastra.

In Kerala, the Natankusa and Hastalaksanadeepika elaborate on theatrical and gestural aspects of the Natya Shastra specifically for Kathakali and related performance forms. In Tamil Nadu, the Bharatarnava and other texts mediate between the Natya Shastra and Bharatanatyam practice.

The transmission to Southeast Asia is equally significant. The Natya Shastra influenced the development of classical dance and theater traditions in Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and other regions that received Indian cultural influence. Thai classical dance (khon), Javanese wayang theater, and Cambodian royal ballet all show adaptations of principles originating in the Natya Shastra, though modified by local aesthetics and cultural contexts.

Modern Scholarship and Translations

Western scholarly attention to the Natya Shastra began in the 19th century with orientalist studies of Sanskrit literature. Complete English translations appeared in the 20th century, making the text accessible to international audiences and enabling comparative aesthetic studies.

Manomohan Ghosh produced the first complete English translation (published 1950-1961), providing extensive notes that explained technical terms and placed the text in historical context. His translation, though sometimes criticized for literalness, remains a standard reference. Adya Rangacharya’s 1986 translation offered a more readable version focusing on theatrical applications. Several partial translations and studies of specific chapters exist, each highlighting different aspects of this complex text.

Modern scholarship has approached the Natya Shastra from multiple perspectives. Performance studies scholars examine how the text’s principles operate in living dance and theater traditions. Music historians trace the development of Indian classical music from the text’s theoretical framework. Philosophers analyze rasa theory’s contributions to aesthetics, comparing it with Western theories of aesthetic experience. Historians use the text as evidence for ancient Indian social life, theater architecture, and cultural practices.

Recent scholarship has increasingly questioned simplistic readings of the text’s dating and authorship. Rather than being composed by a single author at one time, the Natya Shastra likely represents a compilation of accumulated knowledge from multiple sources, edited and organized by scholars working in the “Bharata” tradition. This compositional complexity explains some internal inconsistencies and variations across manuscript traditions.

Feminist scholars have examined the text’s gender politics, noting both progressive elements (women’s participation in performance, detailed attention to female characters) and patriarchal assumptions (certain role restrictions, male gaze in describing feminine beauty). Understanding these complexities provides a more nuanced view of ancient Indian society.

Post-colonial scholars have analyzed how the Natya Shastra was invoked during cultural nationalism and dance revival movements. The text’s authority was mobilized to establish the “classicism” and ancient pedigree of revived dance forms, sometimes obscuring the complex negotiations between textual prescription and actual practice that characterized these revivals.

Contemporary Relevance

Despite its ancient origins, the Natya Shastra remains remarkably relevant to contemporary Indian performing arts. Dance teachers regularly reference the text when training students in hand gestures, facial expressions, and emotional portrayal. Theater directors draw on its dramatic structures and characterization principles. Music scholars study its theoretical framework to understand the historical development of Indian music.

Modern adaptations and reinterpretations continue. Contemporary choreographers create new works based on the 108 karanas, exploring how these ancient movement units can express modern themes. Experimental theater practitioners test the text’s conventions against contemporary sensibilities, sometimes following them and sometimes deliberately subverting them to create new aesthetic effects.

The rasa theory has found applications beyond traditional arts. Film scholars analyze how Indian cinema creates emotional experience through techniques analogous to rasa generation. Comparative aesthetics scholars examine rasa theory alongside Western concepts like catharsis, empathy, and aesthetic distance. Some psychologists have explored whether rasa categories represent universal emotional experiences or culturally specific constructions.

UNESCO’s recognition of various Indian classical dances and their connection to ancient treatises like the Natya Shastra has contributed to heritage preservation efforts. Dance schools and performance institutions receive support explicitly to maintain traditions rooted in the text’s principles.

Internationally, the Natya Shastra has influenced intercultural theater and dance. Directors like Peter Brook and Eugenio Barba have drawn on its concepts in developing their own approaches to actor training and performance. The text’s systematic analysis of how the body communicates meaning offers insights applicable across cultural boundaries.

Debates and Controversies

Several scholarly debates surround the Natya Shastra. The dating question remains unresolved, with estimates varying by a millennium. Some scholars argue for earlier composition (500 BCE or even earlier), citing apparent references to the text in other works and the sophistication of the performance culture it describes, which must have developed over centuries. Others argue for later dating (closer to 200-500 CE), noting the text’s systematic organization characteristic of later shastra literature and absence of clear external references to it before the classical period.

The authorship question is equally complex. “Bharata Muni” may be a historical person, a legendary figure, or a tradition rather than an individual. The text’s internal claim of divine origin reflects its sacred status but complicates historical investigation. Some scholars suggest the text represents accumulated knowledge from performance lineages (parampara) eventually compiled and attributed to a founding figure.

The relationship between textual prescription and actual practice has generated debate. To what extent did historical performers follow the Natya Shastra’s detailed instructions? Evidence suggests considerable variation—the text likely represented an idealized systematic presentation of principles that performers adapted flexibly. The relationship between shastra (theoretical treatise) and prayoga (practical application) in Indian traditions is always complex, with theory and practice mutually informing each other rather than theory simply dictating practice.

Some scholars have questioned whether the performance culture described in the Natya Shastra ever fully existed historically or whether the text represents a synthesized vision bringing together elements from various traditions. The elaborate theater architecture, for instance, may describe an ideal rather than typical performance spaces.

Modern performance practitioners sometimes debate how closely contemporary practice should adhere to Natya Shastra prescriptions. Traditionalists argue for strict adherence as maintaining authentic connection to ancient tradition. Reformers advocate adapting principles to contemporary contexts while preserving essential elements. This tension between tradition and innovation characterizes living arts everywhere but takes specific forms in India given the sacred status accorded to authoritative texts.

Legacy and Significance

The Natya Shastra’s significance for Indian civilization cannot be overstated. As a comprehensive treatment of the performing arts and aesthetic philosophy, it established principles that have guided artistic creation for two millennia. Its influence pervades classical dance, music, and theater, extends to folk and devotional performance traditions, and reaches into modern cinema and popular culture.

Philosophically, the rasa theory represents one of humanity’s most sophisticated attempts to understand how art affects consciousness. Its insights into the relationship between emotion and aesthetic experience, between representation and reception, between technique and transcendence, offer perspectives distinct from but comparable to Western aesthetic theories. The Natya Shastra demonstrates that ancient India developed systematic philosophical aesthetics as rigorous as its famous logical and metaphysical philosophies.

Culturally, the text embodies a characteristic Indian approach to knowledge—systematic classification, elaborate detail, integration of practical technique with philosophical understanding, and transmission through lineages. The Natya Shastra is not merely a historical document but a living tradition actively shaping contemporary artistic practice.

For world culture, the Natya Shastra represents an alternative performance aesthetic that enriches global understanding of theatrical possibilities. Its emphasis on symbolic gesture, stylized movement, and emotional essence rather than realistic representation offers contrasts with Western theatrical traditions while finding parallels in other Asian performance cultures it influenced.

The text’s survival through centuries of oral and manuscript transmission, its continuous study and commentary, its embodiment in living performance traditions, and its relevance to contemporary artists all testify to its enduring power. The Natya Shastra remains what it has always been—a comprehensive guide to the performing arts, a philosophical exploration of aesthetic experience, and a testament to the sophistication of ancient Indian civilization.

Note: Dating estimates for the Natya Shastra vary significantly across scholarly sources, with most authorities agreeing on a compilation period between 200 BCE and 200 CE, though some estimates extend from 500 BCE to 500 CE. This article uses the more conservative central estimate while acknowledging the uncertainty.

Sources: The primary source is the Natya Shastra text itself in various translations. Secondary scholarly sources include studies of Indian aesthetics, classical performance traditions, and Sanskrit drama. All uncertain information has been marked as such in the text.