Ramcharitmanas

Tulsidas's 16th-century Awadhi epic retelling Valmiki's Ramayana, a cornerstone of North Indian devotional literature and Hindu culture.

Gallery

Gallery

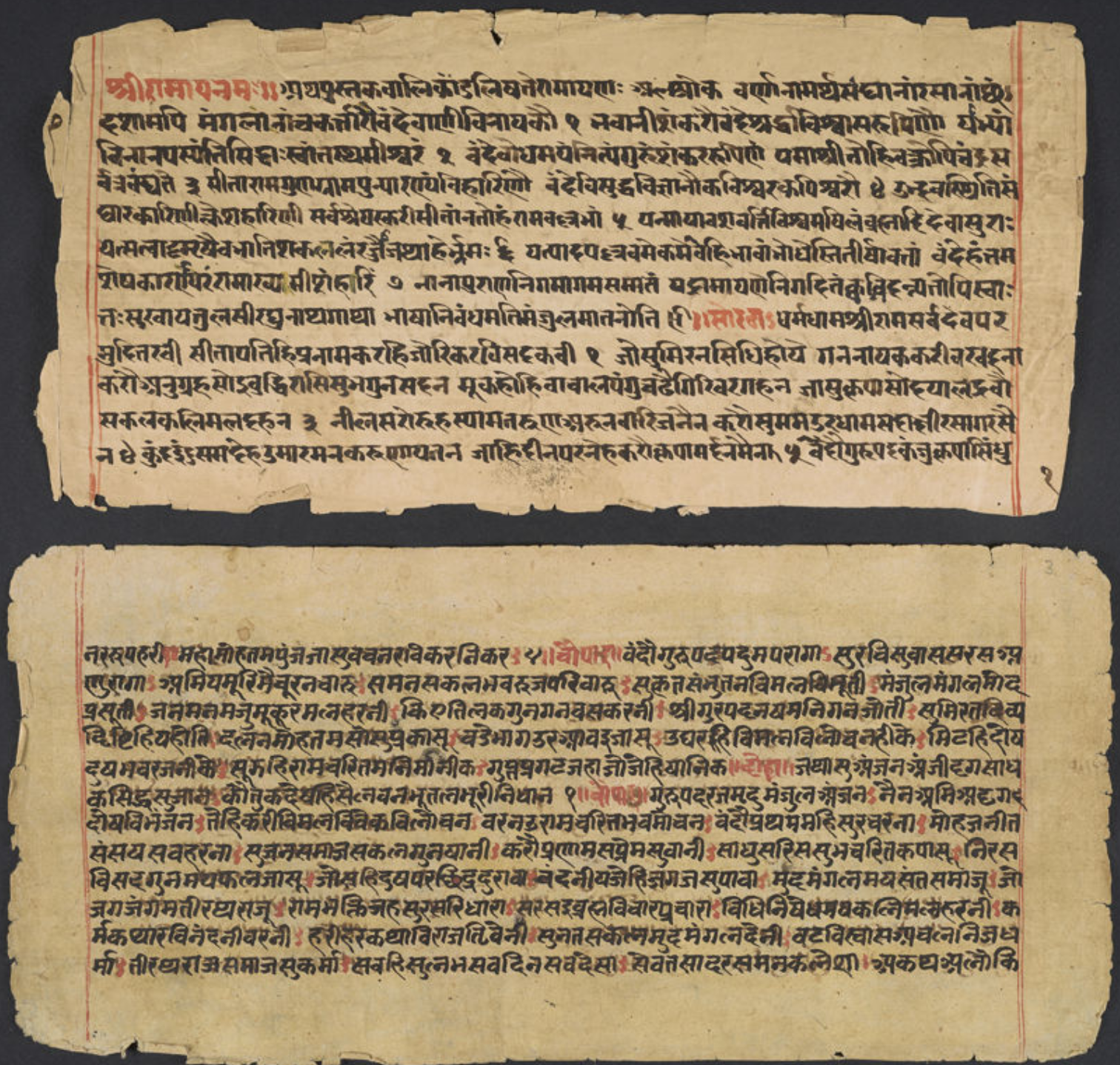

A 19th-century manuscript of Ramcharitmanas by scribe Jānak De

Artistic depiction of scenes from the Ramayana tradition (LACMA collection)

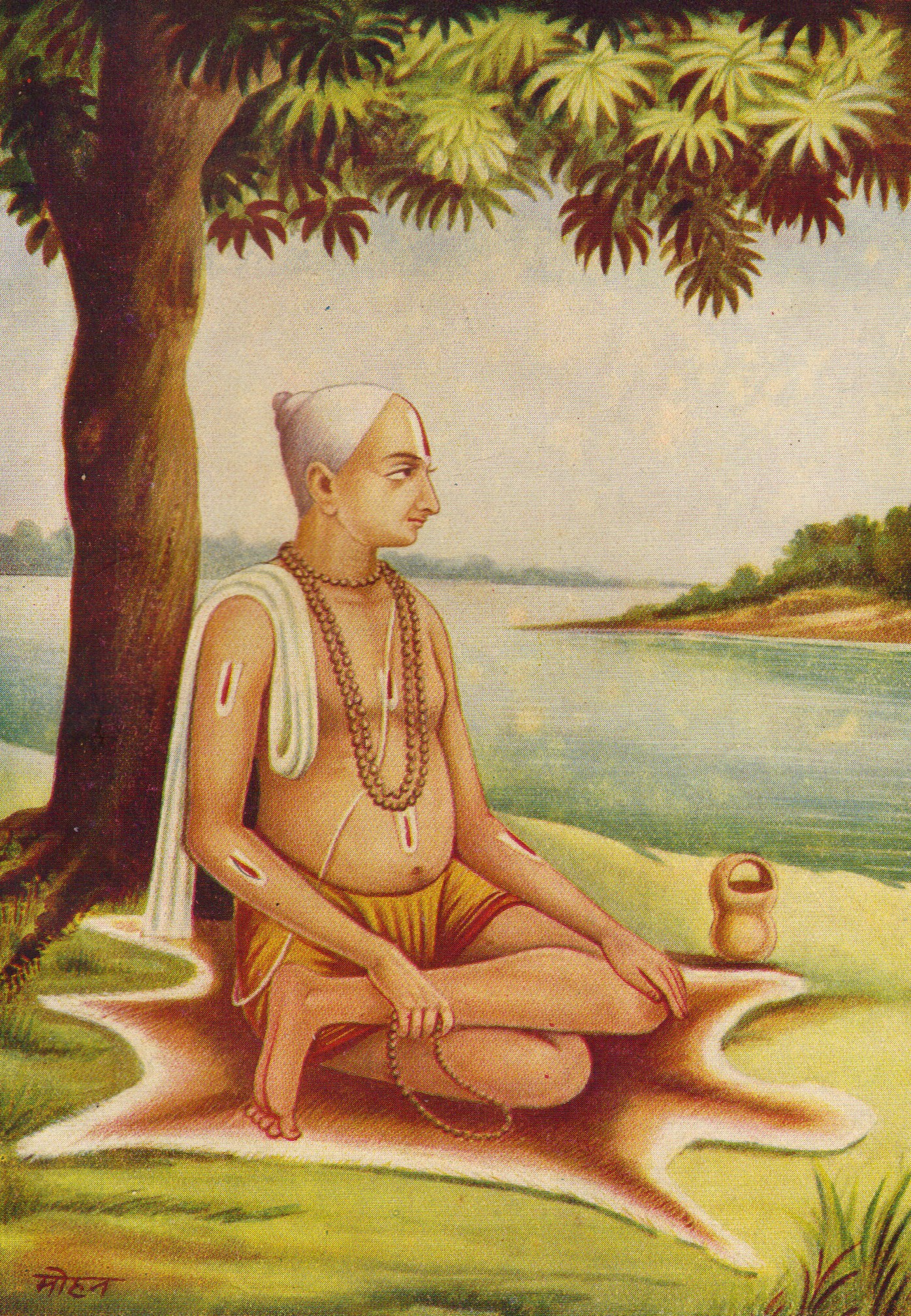

Portrait of Tulsidas, the composer of Ramcharitmanas (1949)

A traditional edition of Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas

Introduction

The Ramcharitmanas, literally “The Lake of the Deeds of Rama,” stands as one of the most influential and beloved works in the history of Indian literature. Composed by the 16th-century poet-saint Goswami Tulsidas in the Awadhi language, this epic poem has transcended its literary origins to become a living scripture that shapes the religious, cultural, and social life of millions across North India and beyond. Unlike its Sanskrit predecessor, Valmiki’s Ramayana, which remained largely confined to scholarly circles, Tulsidas’s masterpiece brought the story of Lord Rama into the homes and hearts of common people, democratizing access to sacred narrative through vernacular expression.

Written during a pivotal period of India’s medieval history, when the bhakti movement was reshaping Hindu devotional practice and vernacular literature was gaining unprecedented prestige, the Ramcharitmanas represents a synthesis of classical tradition and popular accessibility. Tulsidas did not merely translate Valmiki’s ancient epic; he reimagined it through the lens of medieval devotional theology, creating a work that speaks simultaneously to sophisticated philosophical inquiry and simple heartfelt devotion. The text’s influence extends far beyond literature—it has shaped temple rituals, inspired countless artistic traditions, provided the foundation for the popular Ramlila dramatic performances, and continues to be recited daily in homes and temples throughout India.

The Ramcharitmanas occupies a unique position in Indian cultural history as both a religious text and a literary masterpiece. Its accessibility in the Awadhi dialect, coupled with its profound theological insights and poetic beauty, has made it perhaps the most widely known version of the Rama story among Hindi-speaking populations. The work embodies the essence of Rama bhakti (devotion to Rama), presenting the divine prince not merely as an avatar of Vishnu but as the supreme reality accessible through loving devotion.

Historical Context

The composition of the Ramcharitmanas occurred during the late 16th century, traditionally dated to 1574 CE, though scholars debate the precise chronology. This period witnessed significant religious and cultural transformations across the Indian subcontinent. The bhakti movement, which had emerged in South India centuries earlier, had spread northward, fundamentally altering Hindu devotional practice by emphasizing personal devotion over ritual orthodoxy and making spirituality accessible across caste and educational boundaries.

The Mughal Empire under Akbar (r. 1556-1605) dominated North India politically, creating a complex cultural environment where Persian and Turkic influences interacted with indigenous traditions. Yet this was also a period of remarkable vernacular literary flourishing. Poets and saints across North India were composing devotional literature in regional languages—Kabir in eastern Hindi dialects, Surdas in Braj Bhasha, Mirabai in Rajasthani—challenging the monopoly of Sanskrit as the sole language worthy of religious expression.

Varanasi (Banaras), the city most closely associated with Tulsidas and the composition of the Ramcharitmanas, served as a major center of Sanskrit learning and Hindu orthodoxy. The choice to compose a major religious work in Awadhi rather than Sanskrit within this bastion of traditional scholarship represented a significant statement about linguistic accessibility and devotional priorities. The bhakti poets’ use of vernacular languages was not merely practical but theological—it embodied the principle that divine grace was available to all devotees regardless of their education or social status.

The specific historical circumstances surrounding the Ramcharitmanas’s composition remain partially obscure, wrapped in devotional tradition and hagiography. According to traditional accounts, Tulsidas received divine inspiration to compose the work, with some traditions claiming he saw Hanuman himself who encouraged the project. Whether or not such supernatural elements are accepted, the work clearly emerged from a context where Rama devotion had deep roots in North Indian religiosity and where vernacular religious literature was gaining acceptance and prestige.

Creation and Authorship

Tulsidas (traditionally dated 1532-1623 CE), also known as Goswami Tulsidas, ranks among the greatest poets in Indian literary history. Born into a Brahmin family in the region of present-day Uttar Pradesh, Tulsidas lived during an era of religious ferment and literary innovation. Traditional hagiographies present him as a devoted scholar who mastered Sanskrit literature before turning to vernacular composition, though historical details about his life remain contested among scholars.

The creation story of the Ramcharitmanas is itself embedded in devotional tradition. According to popular accounts, Tulsidas composed the work in Varanasi over a period of two years, seven months, and twenty-six days, beginning on Rama Navami (Rama’s birthday) in 1574 CE. While these precise details may be hagiographical embellishments, they reflect the text’s sacred status in popular imagination. The choice of Awadhi—the language associated with Ayodhya, Rama’s capital—was deliberate, linking the text linguistically to its narrative setting.

Tulsidas’s approach to his source material demonstrates sophisticated literary craftsmanship. While Valmiki’s Ramayana provided the primary narrative framework, Tulsidas drew upon a rich tradition of Rama literature in Sanskrit and vernacular languages, including the Adhyatma Ramayana (a philosophical retelling emphasizing Vedantic themes) and various Puranic versions. The poet freely adapted, expanded, and reimagined his sources, creating a work that is simultaneously traditional and original.

The compositional process reflected medieval devotional aesthetics. Tulsidas framed his narrative as a series of conversations—between Shiva and Parvati, between the sage Yajnavalkya and Bharadvaja, between Kakabhushundi the crow and Garuda the eagle—creating multiple narrative levels that allow philosophical commentary alongside storytelling. This structural sophistication coexists with accessible language and memorable verses that could be easily memorized and recited by devotees of all educational backgrounds.

The poet’s genius lay in his ability to maintain narrative momentum while incorporating theological depth, ethical instruction, and devotional intensity. His Rama emerges as simultaneously human and divine, majestic and accessible, embodying both royal virtue (maryada) and divine grace (kripa). Tulsidas’s Hanuman, in particular, became the archetypal devotee, demonstrating the power of selfless service and unwavering devotion.

Structure and Content

The Ramcharitmanas is organized into seven books (kāṇḍas), mirroring the traditional structure of Valmiki’s Ramayana: Bal Kanda (Book of Childhood), Ayodhya Kanda (Book of Ayodhya), Aranya Kanda (Book of the Forest), Kishkindha Kanda (Book of Kishkindha), Sundar Kanda (Book of Beauty), Lanka Kanda (Book of Lanka), and Uttar Kanda (Book of the Latter Part). However, Tulsidas’s treatment of this traditional structure reveals his distinct priorities and theological vision.

The Bal Kanda establishes the devotional framework through multiple prologues before narrating Rama’s birth and childhood. Tulsidas begins with invocations and philosophical discussions that frame the entire work as an act of devotion. The narrative then recounts Rama’s childhood in Ayodhya, his education, and his marriage to Sita following the famous bow-breaking episode. This section establishes Rama’s divine nature while emphasizing his accessibility to devotees.

The Ayodhya Kanda, often considered the emotional heart of the text, narrates the events leading to Rama’s exile: King Dasharatha’s promise to his wife Kaikeyi, Rama’s willing acceptance of fourteen years’ banishment, Sita and Lakshmana’s insistence on accompanying him, and Dasharatha’s death from grief. Tulsidas’s treatment of these episodes emphasizes dharma (righteous duty) even when it conflicts with personal happiness, while portraying the depth of familial love and devotion.

The Aranya Kanda follows Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana’s forest exile, including encounters with sages, demons, and the pivotal event of Sita’s abduction by Ravana. This section explores themes of devotion through the story of Shabari, a tribal woman whose simple devotion pleases Rama more than elaborate Brahmanical rituals, exemplifying the bhakti movement’s inclusive ethos.

The Kishkindha Kanda narrates Rama’s alliance with the monkey kingdom, particularly his friendship with Sugriva and his meeting with Hanuman, who becomes the ideal devotee in the Ramcharitmanas tradition. The monkey army’s organization and the search for Sita prepare for the epic’s climactic conflict.

The Sundar Kanda is unique in focusing primarily on Hanuman. His journey to Lanka, meeting with Sita, burning of Lanka, and return to Rama showcase devotional service as the highest spiritual path. This book has become particularly popular as an independent text for recitation, believed to bring blessings and remove obstacles.

The Lanka Kanda describes the war between Rama’s army and Ravana’s forces, culminating in Ravana’s death and Sita’s rescue. Tulsidas emphasizes divine intervention and the ultimate victory of dharma over adharma (unrighteousness), while also portraying Ravana as a complex character whose devotion and learning were undermined by pride and desire.

The Uttar Kanda narrates Rama’s return to Ayodhya, his coronation, and his righteous rule (Rama Rajya), which becomes the ideal of perfect governance in Hindu political imagination. Unlike Valmiki’s version, Tulsidas’s Uttar Kanda is relatively brief and omits the controversial episode of Sita’s second exile, choosing instead to emphasize the establishment of dharmic order and the possibility of spiritual liberation through devotion to Rama.

Throughout these seven books, Tulsidas weaves approximately 12,800 lines of poetry in various Awadhi meters, primarily the chaupai (a four-line stanza) interspersed with dohas (couplets) that often provide moral summaries or philosophical insights. This metrical variety creates a rhythmic texture that enhances both oral recitation and memorization.

Themes and Philosophical Content

The Ramcharitmanas operates on multiple thematic levels simultaneously, making it accessible to readers seeking simple devotional narrative while offering sophisticated philosophical and theological content for more contemplative study.

Bhakti (Devotion) stands as the central theme. Tulsidas presents devotion to Rama as the supreme spiritual path, accessible to all regardless of caste, education, or ritual knowledge. Unlike paths requiring extensive learning or ascetic practice, bhakti is portrayed as simple, joyful, and immediate. Hanuman exemplifies perfect devotion—selfless, humble, focused entirely on serving Rama without concern for personal benefit or recognition. This democratization of spirituality reflected the bhakti movement’s core conviction that divine grace responded to sincere love rather than social status or ritual correctness.

Dharma (righteousness, duty, cosmic order) pervades the narrative. Rama embodies maryada (dignified adherence to proper boundaries), accepting exile to honor his father’s word, treating all beings with respect, and establishing just governance. The text explores tensions between different dharmic obligations—filial duty versus marital love, kingly responsibility versus personal happiness—presenting dharma not as rigid rule-following but as thoughtful response to complex situations guided by righteousness and compassion.

The Nature of the Divine receives sophisticated treatment. Tulsidas presents Rama as simultaneously saguna (with attributes—the human prince) and nirguna (without attributes—the supreme, formless Brahman). This theological sophistication reconciles devotional theism with Vedantic non-dualism, allowing devotees to worship Rama’s personal form while understanding him as the ultimate reality beyond all forms. The frame narratives, particularly the discussions between Shiva and Parvati, explicitly address these philosophical dimensions.

Social Ethics emerge through numerous episodes demonstrating ideal behavior across relationships: between parents and children, husbands and wives, brothers, friends, and rulers and subjects. Rama’s treatment of Shabari challenges caste hierarchy, while his brotherhood with Sugriva and Hanuman transcends species boundaries. The text advocates humility, service, truthfulness, and compassion as fundamental virtues.

The Power of God’s Name receives special emphasis. Tulsidas frequently asserts that reciting Rama’s name itself brings spiritual benefit, salvation, and practical help in times of difficulty. This nama-bhakti (devotion through reciting the divine name) became central to popular Hindu practice, making spiritual advancement accessible even to those who couldn’t study texts or perform elaborate rituals.

Maya (divine illusion) and the nature of worldly existence appear in philosophical passages, particularly in discussions between Rama and Lakshmana or in the frame narratives. The text acknowledges the world as both real (from the devotee’s perspective) and ultimately illusory (from the perspective of ultimate truth), resolving this paradox through devotional surrender.

Literary Artistry and Language

Tulsidas’s literary genius manifests in his masterful use of the Awadhi language, his sophisticated narrative structure, and his ability to create memorable, quotable verses that have entered popular consciousness.

Linguistic Choice: The decision to compose in Awadhi rather than Sanskrit or the more literary Braj Bhasha was revolutionary. Awadhi, spoken in the Ayodhya region, connected the text linguistically to its narrative setting while making it accessible to a broader audience. Tulsidas demonstrated that vernacular languages could express subtle philosophical concepts and create aesthetic beauty equal to Sanskrit.

Metrical Variety: The primary meter, chaupai, provides narrative momentum with its four-line stanzas, while dohas (couplets) punctuate the narrative with memorable aphorisms and philosophical insights. Other meters including soratha, chhand, and harigitika add variety and mark significant moments. This metrical diversity creates a rhythmic texture that enhances both meaning and memorability.

Imagery and Description: Tulsidas employs rich imagery drawn from North Indian landscape, culture, and daily life. His descriptions of Rama’s beauty, Sita’s grace, Hanuman’s devotion, and natural settings create vivid sensory experiences. The poet balances elaborate poetic ornamentation with accessible language, making complex ideas concrete through familiar imagery.

Characterization: While following traditional narrative, Tulsidas develops characters with psychological depth. His Rama combines royal dignity with compassionate accessibility. Sita embodies strength and devotion rather than passive femininity. Lakshmana’s devotion and occasional impulsiveness, Bharata’s profound love for his brother, Hanuman’s humility despite enormous power—each character receives nuanced treatment.

Narrative Framing: The multiple narrative levels—stories within stories, conversations between divine beings discussing Rama’s tale—create sophisticated structure while allowing philosophical commentary without interrupting narrative flow. This technique, borrowed from Puranic literature, enables Tulsidas to address different audiences simultaneously.

Memorable Verses: Countless lines from the Ramcharitmanas have become proverbial in Hindi-speaking regions. Verses about devotion, righteousness, and practical wisdom are quoted in daily conversation, cited in speeches, and inscribed on buildings. This integration into living language testifies to the work’s profound cultural penetration.

Cultural Significance and Impact

The Ramcharitmanas has shaped North Indian culture more profoundly than perhaps any other single literary work. Its influence extends across religious practice, performing arts, social values, language, and popular culture.

Religious Practice: The text functions as a living scripture. Daily recitation (paath) of the Ramcharitmanas is considered spiritually meritorious. Nine-day complete readings (Akhand Paath) mark important occasions. The Sundar Kanda is recited on Tuesdays and Saturdays to invoke blessings and remove obstacles. Many Hindus memorize extensive passages, and the work accompanies life-cycle rituals from birth to death.

Ramlila Tradition: The Ramcharitmanas provides the primary script for Ramlila, dramatic enactments of Rama’s story performed annually during the festival season leading to Dussehra. These performances, ranging from village productions to elaborate month-long presentations, make the text’s narrative and values accessible to even non-literate audiences, creating shared cultural experience across communities.

Language and Literature: The Ramcharitmanas elevated Awadhi to literary prestige and influenced the development of modern Hindi. Its vocabulary, idioms, and phrases permeate Hindi discourse. The work inspired countless later poetic and prose retellings, commentaries, and devotional compositions, establishing a rich tradition of Rama literature in North Indian languages.

Social Impact: While containing elements reflecting medieval social hierarchies, the text’s emphasis on accessible bhakti regardless of caste or learning supported more inclusive religious practice. Episodes like Rama’s acceptance of Shabari’s offering challenged ritual exclusivism. The ideal of Rama Rajya (Rama’s rule) has influenced political discourse, representing visions of just, harmonious governance.

Visual Arts: The Ramcharitmanas inspired extensive artistic traditions. Manuscript illustrations, temple wall paintings, popular prints, and calendar art depict its scenes. The text’s descriptions shaped iconographic conventions for representing Rama, Sita, Hanuman, and other characters in sculpture and painting.

Musical Traditions: The text’s verses are set to classical and devotional musical forms. Ramcharitmanas recitation with musical accompaniment (sangit paath) constitutes a distinct performance tradition. Bhajans (devotional songs) drawn from or inspired by the text form a major component of North Indian devotional music.

Manuscript Tradition and Textual History

The textual history of the Ramcharitmanas reflects both its sacred status and the challenges of manuscript transmission before printing technology. Early manuscripts, copied by hand and transmitted through generations, show variations in readings, though the text’s core remains stable.

The earliest surviving manuscripts date from the 17th century, decades after Tulsidas’s traditional death date (1623 CE). These manuscripts, written in Devanagari script, were typically produced by professional scribes or devoted scholars. The care taken in copying reflects the text’s revered status—errors were considered spiritually dangerous, and copying the text itself was seen as meritorious religious practice.

Manuscript variations primarily involve minor verbal differences rather than major narrative changes. Different manuscript families reflect regional transmission patterns across North India. Some variations may represent intentional “improvements” by scribes, while others result from copying errors or attempts to clarify difficult passages.

The introduction of printing in the 19th century transformed access to the Ramcharitmanas. Early printed editions, beginning in the 1810s, made the text widely available, standardizing the version known to most readers today. The Gita Press edition from Gorakhpur, first published in 1923, became perhaps the most influential modern version, distributed in millions of copies and shaping popular understanding of the text.

Modern scholarly editions have attempted to establish critical texts based on careful manuscript comparison. However, given the Ramcharitmanas’s status as living scripture rather than merely historical artifact, devotional editions often prioritize accessibility and traditional readings over strict textual criticism.

The manuscript tradition includes not only the text itself but extensive commentary literature. Traditional scholars composed tikas (commentaries) explaining difficult passages, elaborating philosophical points, and connecting verses to broader Hindu theology. This commentary tradition, beginning in Tulsidas’s own lifetime, continues today with modern interpretations addressing contemporary concerns.

Scholarly Reception and Interpretation

Academic engagement with the Ramcharitmanas has evolved considerably, particularly from the late 19th century onward as Western scholarly methods and nationalist literary criticism developed in India.

Historical and Biographical Study: Scholars have attempted to establish accurate biographical information about Tulsidas and precise dating for the Ramcharitmanas. This project faces challenges from the accretion of hagiographical traditions around the poet. Critical consensus places composition in the late 16th century, though exact dates remain debated. Biographical reconstruction must distinguish historical kernel from devotional elaboration.

Literary Analysis: Literary scholars have examined the Ramcharitmanas’s artistic qualities—its narrative structure, characterization, poetic techniques, and linguistic sophistication. Comparative studies explore relationships to Valmiki’s Ramayana, other vernacular Ramayanas, and contemporary bhakti literature. The text’s successful combination of accessibility and sophistication attracts continued scholarly attention.

Theological Interpretation: Religious scholars analyze the Ramcharitmanas’s theological positions within Hindu thought. The text’s synthesis of devotional theism (bhakti) with Vedantic non-dualism (advaita), its emphasis on nama-bhakti, and its presentation of Rama as supreme reality receive philosophical examination. Debates continue about whether Tulsidas’s theology should be classified as qualified non-dualism (vishishtadvaita), dualistic devotionalism (dvaita), or a distinctive synthesis.

Social and Gender Analysis: Modern scholars examine the text’s social implications. While the Ramcharitmanas contains inclusive devotional elements, it also reflects medieval social hierarchies. Contemporary scholarship debates the text’s treatment of gender, particularly through Sita’s characterization, and its implications for caste hierarchy despite its bhakti emphasis on devotional equality. These interpretations often reflect contemporary social concerns projected onto historical texts.

Political Readings: The Ramcharitmanas has been read through political lenses, particularly regarding the concept of Rama Rajya (Rama’s ideal rule). Colonial-era nationalists invoked Rama Rajya to critique British rule. Mahatma Gandhi frequently cited the text and used Rama Rajya as shorthand for ideal governance, though he interpreted it in universalist moral terms. Later political movements have appropriated the text toward varied, sometimes conflicting, agendas.

Reception Studies: Scholars examine how different communities have understood and used the Ramcharitmanas across centuries. Studies of oral recitation practices, performance traditions, devotional uses, and the text’s role in shaping Hindu identity contribute to understanding its cultural function beyond literary analysis.

Translations and Global Reach

The Ramcharitmanas has been translated into numerous languages, both within India and internationally, though translation presents significant challenges given the text’s linguistic richness, cultural specificity, and devotional register.

Indian Language Translations: The text has been translated into most major Indian languages including Hindi (since Awadhi is not identical to modern standard Hindi), Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam. These translations serve diverse purposes—some aim for literal accuracy for scholarly study, others prioritize accessibility for devotional reading, and still others attempt to recreate the original’s poetic qualities in the target language. Translation into Hindi is particularly significant given Awadhi’s relationship to modern Hindi; such translations navigate between preserving historical linguistic flavor and ensuring contemporary comprehension.

English Translations: Multiple English translations exist, each reflecting different priorities. Some early translations by Orientalist scholars like F.S. Growse (1877-1878) approached the text primarily as cultural document. Later translations by Indian scholars including R.C. Prasad and Gita Press editions aim to make the text’s devotional content accessible to English readers while providing explanatory notes. Recent scholarly translations attempt to convey both literary artistry and theological depth. The challenge in English translation involves not only linguistic transfer but bridging vast cultural distances—Sanskrit theological concepts, North Indian social contexts, and devotional sensibilities require extensive contextualization for non-Indian readers.

Global Diaspora: Indian diaspora communities worldwide use the Ramcharitmanas to maintain cultural and religious connections. Recitation sessions, Ramlila performances, and study groups occur in Hindu communities from Trinidad to Fiji, from the United Kingdom to the United States. The text serves as cultural anchor, preserving linguistic heritage and transmitting values across generations in diaspora contexts.

Academic Circulation: Translation into European languages (including French, German, and Italian) has facilitated academic study within comparative religion, South Asian studies, and world literature contexts. Scholarly translations emphasize accessibility for non-specialist readers while maintaining scholarly accuracy, supported by extensive annotation explaining cultural and religious contexts.

Contemporary Relevance and Adaptations

The Ramcharitmanas remains vibrantly relevant in contemporary India and global Hindu communities, continuously adapted to new media and contexts while retaining its devotional core.

Digital Presence: The text is extensively available online—full text websites, recitation apps, audio and video recordings, and digital commentaries make the Ramcharitmanas more accessible than ever. Smartphone apps provide daily verses, search functions, and multimedia features. Online platforms host scholarly discussions alongside devotional interpretations, creating new modes of engagement with this ancient text.

Television and Film: Television serializations, most famously Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan (1987-1988), drew extensively from the Ramcharitmanas alongside other sources, reaching massive audiences. This series significantly shaped popular understanding of Rama’s story for an entire generation. Animated versions introduce the narrative to children. These adaptations demonstrate the text’s narrative power while sometimes simplifying its theological complexity.

Musical Adaptations: Contemporary musicians create new settings for Ramcharitmanas verses, from classical renditions to devotional pop. Bhajan singers like Mukesh, Anup Jalota, and many others have made recordings featuring the text’s verses. These musical adaptations introduce the work to younger generations and new audiences through familiar contemporary styles.

Political and Social Discourse: The Ramcharitmanas and its concept of Rama Rajya continue to feature in Indian political discourse, invoked across the political spectrum with different interpretations. Social reformers cite passages emphasizing equality and devotional accessibility, while others invoke different verses toward different ends. This political use, while sometimes controversial, demonstrates the text’s continued cultural centrality.

Educational Context: The Ramcharitmanas features in school and university curricula for Hindi literature, religious studies, and Indian cultural history. Academic conferences, scholarly publications, and university courses continue examining the text from evolving critical perspectives. This scholarly attention coexists with devotional use, the text simultaneously functioning as object of academic study and living scripture.

Interfaith Dialogue: The Ramcharitmanas’s emphasis on ethical living, devotion, and righteous conduct provides common ground for interfaith conversation. Its accessibility and moral teachings allow engagement across religious boundaries, even as its specifically Hindu theological content remains central to its identity.

Preservation and Conservation Efforts

Preserving the Ramcharitmanas involves both physical conservation of historical manuscripts and cultural preservation of associated traditions.

Manuscript Conservation: Historical manuscripts reside in museums, libraries, and private collections across India. Institutions like the Tulsi Smarak Bhawan in Varanasi house important collections. Conservation efforts address deterioration from age, climate, and handling. Digitization projects photograph and scan manuscripts, creating permanent records and enabling scholarly access without risking physical damage to fragile originals.

Cultural Preservation: Efforts to preserve Ramlila traditions, recitation practices, and associated performing arts ensure the Ramcharitmanas’s living cultural context continues. Government programs, cultural organizations, and community initiatives support traditional performers, document regional variations, and encourage younger generation participation in these traditions.

Educational Initiatives: Programs teaching Awadhi language help preserve the ability to read the Ramcharitmanas in its original tongue. As modern Hindi diverges from historical Awadhi, such linguistic preservation becomes increasingly important for authentic engagement with Tulsidas’s language.

Documentation Projects: Ethnographic documentation of how different communities use the Ramcharitmanas—recitation practices, ritual contexts, performance traditions—creates records of these cultural practices. Such documentation serves both scholarly purposes and cultural preservation, capturing knowledge before potential loss.

Conclusion

The Ramcharitmanas stands as a monumental achievement in Indian literature and devotional expression, successfully synthesizing high literary artistry with accessible devotional content, ancient narrative tradition with medieval bhakti theology, and philosophical sophistication with popular appeal. Tulsidas’s 16th-century masterpiece has shaped Hindu religious practice, influenced North Indian cultural values, inspired artistic and performing traditions, and provided millions with a pathway to divine grace through devotional engagement.

The text’s enduring relevance stems from multiple factors: its narrative power, poetic beauty, theological depth, ethical wisdom, and emotional resonance. Unlike works that remain frozen in their historical moment, the Ramcharitmanas lives dynamically in continuing recitation, performance, adaptation, and reinterpretation. It functions simultaneously as scripture and literature, ancient text and contemporary cultural force, object of scholarly analysis and vessel of devotional experience.

As India navigates modernity’s challenges while seeking to preserve cultural heritage, the Ramcharitmanas demonstrates how traditional texts can maintain relevance through organic evolution rather than rigid preservation. New media, contemporary interpretations, and changing social contexts generate fresh engagements with Tulsidas’s epic, ensuring its continued vitality for future generations while honoring its historical depth and devotional core.

For scholars, the Ramcharitmanas offers inexhaustible resources for studying medieval Indian literature, bhakti theology, vernacular literary development, and cultural history. For devotees, it provides daily spiritual nourishment, a guide to righteous living, and a path to divine grace. This dual function—as object of study and instrument of devotion—exemplifies the richness of India’s literary and religious traditions, where aesthetic beauty and spiritual depth intertwine inseparably.

The Ramcharitmanas ultimately transcends categorization as merely historical artifact or religious text. It remains a living cultural force that continues shaping how millions understand divinity, morality, devotion, and human purpose. Tulsidas’s achievement lies not only in his poetic skill or theological insight but in creating a work that speaks with equal power to heart and mind, to scholar and simple devotee, across centuries and changing contexts—a true testament to the enduring power of great literature in the service of transcendent truth.

_1s3qpl.webp)