Measuring the Immeasurable: The Epic Quest to Map India

The fever returned in the monsoon season, as it always did. William Lambton felt it creeping through his bones as he bent over the theodolite, squinting through sweat and rain to sight the distant signal station eighteen miles away. Around him, the coastal plains of southern India stretched endlessly, a green expanse that had already consumed three years of his life and the lives of several of his men. The massive brass instrument before him—weighing over half a ton—represented the most precise surveying equipment the early 19th century could produce. Yet here, in the suffocating heat of 1805, precision seemed almost laughable. The very earth beneath his observation platform seemed to shimmer and shift in the heat, bending light itself, mocking his attempts to measure it with mathematical certainty.

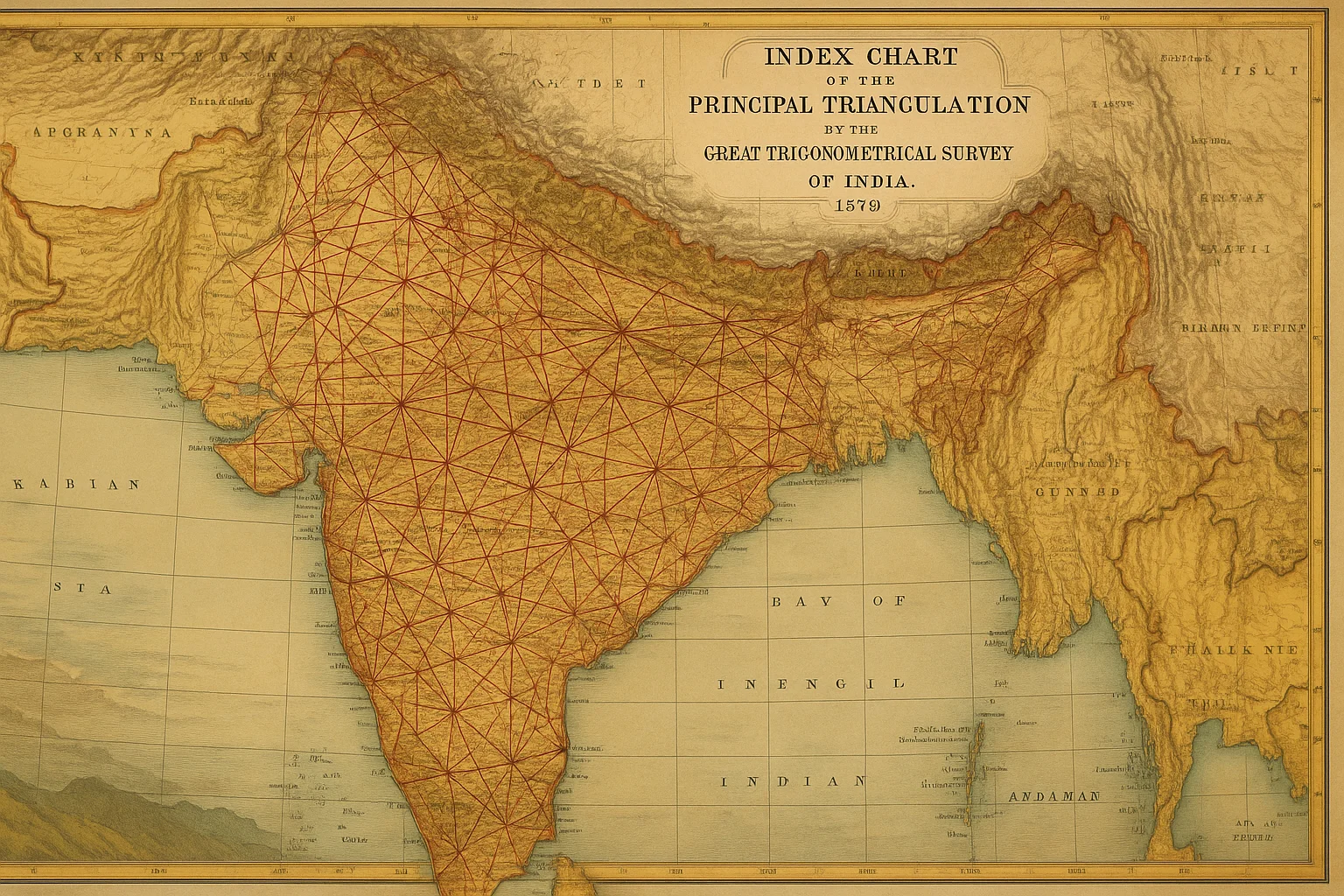

But Lambton was not a man who acknowledged mockery, from nature or otherwise. A British infantry officer serving the East India Company, he had begun this audacious project three years earlier with a vision that struck his contemporaries as either brilliant or mad: to measure the entire Indian subcontinent using the principles of trigonometry, creating a vast network of triangles that would eventually cover everything from the southern tip of the peninsula to the Himalayan peaks thousands of miles north. Each triangle would be measured with such precision that the accumulated error over hundreds of miles would amount to mere inches. It was a dream of Enlightenment rationality imposed upon an ancient land, an attempt to reduce the chaotic, teeming vastness of India to numbers, angles, and coordinates.

The rain intensified, drumming against the canvas shelter erected over the theodolite. Lambton’s hands, cramped from hours of minute adjustments, continued their work. He had learned that in India, you worked when conditions allowed, not when they were ideal. Ideal conditions rarely came. The monsoon would last months. The measurements could not wait. Behind him, his team of Indian assistants—surveyors, calculators, and laborers whose names history would largely forget—stood ready with their notebooks, prepared to record whatever numbers their British commander wrested from the resistant landscape. They had learned to read his moods, to know when he needed silence and when he needed their observations. They had learned, too, that this strange project consumed men’s lives entirely, that years would pass while they trudged from station to station, always measuring, always calculating, never quite finished.

What none of them knew, as the rain fell and the theodolite captured another bearing, was that this project would outlast Lambton himself. It would outlast the next surveyor general and the one after that. It would consume sixty-nine years—nearly seven decades—becoming one of the longest continuous scientific projects ever undertaken. It would map an empire with unprecedented accuracy, transform cartography, and eventually make a discovery that would capture the world’s imagination: the identification of Peak XV, a distant mountain in the Himalayas that calculations would prove to be the highest point on Earth. The world would come to know it as Everest, though that name lay decades in the future, as distant and uncertain as the peaks themselves, hidden somewhere beyond the rain and heat and the endless work of measurement.

The World Before: An Empire Without Maps

At the turn of the 19th century, the British East India Company found itself ruling vast territories it could not accurately describe. Since its victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the Company had transformed from a trading concern into a political power, accumulating Indian territories through conquest, treaty, and manipulation. By 1802, it controlled much of southern and eastern India, with influence extending into the central regions. Yet despite this territorial expansion, the Company possessed no accurate maps of its holdings. Existing charts were compilations of rough sketches, travelers’ estimates, and wishful thinking. Distances between cities might be wrong by dozens of miles. The shapes of coastlines were approximate. The locations of interior regions were often pure guesswork.

This geographical ignorance posed serious practical problems. Military campaigns required accurate distance calculations for supply lines and troop movements. Tax collection depended on knowing the actual extent of agricultural lands. Trade routes needed reliable measurements. The Company’s administrators in Calcutta and Madras issued orders based on maps that might place cities in entirely wrong positions relative to each other. When armies marched, they often discovered that their maps bore little resemblance to the actual terrain.

Previous surveying efforts had been limited and localized. Various Company officers had attempted to map particular regions for specific military or administrative purposes, but these surveys used inconsistent methods and reference points. A map made for the Madras Presidency might use different baselines and measurements than one made for Bengal, making it impossible to fit them together into a coherent whole. Some surveyors estimated distances by timing how long it took to travel between points—a method that varied with weather, road conditions, and the mood of the pack animals. Others used simple compass bearings without accounting for magnetic variation or the curvature of the Earth.

The Indian subcontinent itself presented extraordinary surveying challenges. Its sheer size dwarfed anything European surveyors had attempted. It contained every type of terrain imaginable: coastal plains and river deltas, dense jungles, arid deserts, rolling agricultural lands, and finally the Himalayas—mountain ranges so vast and high they created their own weather systems. Temperatures ranged from the scorching heat of Rajasthan summers to the freezing conditions of high-altitude passes. Monsoons made travel impossible for months. Diseases—malaria, cholera, typhoid, dysentery—killed more Europeans than military action ever did.

Yet by 1802, the technological capability to conduct a truly scientific survey finally existed. Theodolites had been refined to allow extremely precise angle measurements. Chronometers could accurately determine longitude. The mathematics of triangulation—using measured angles and one carefully measured baseline to calculate distances across large areas—was well understood in theory. What was needed was someone with the vision to apply these tools on an unprecedented scale, and the obsessive determination to see the project through.

India in 1802 was also in the midst of profound political transformation. The Maratha Confederacy, which had dominated much of India through the late 18th century, was fragmenting through internal conflicts. The Mughal Empire, though nominally existing, had been reduced to symbolic authority over little more than Delhi itself. Into this power vacuum, the British East India Company was expanding aggressively under Governor-General Richard Wellesley. This expansion would continue throughout the survey’s duration, meaning the surveyors would often find themselves measuring territories that had only recently come under British control, and sometimes measuring during active military campaigns.

The survey would thus serve multiple purposes. Officially, it was a scientific endeavor, part of the Enlightenment project to measure and understand the natural world. Practically, it was a tool of imperial control, a way to make India legible to its new rulers. The precise maps it would produce would facilitate military operations, tax collection, and economic exploitation. Yet it would also represent a genuine scientific achievement, applying mathematical rigor to a problem of enormous scale and complexity. This tension between scientific ambition and imperial utility would characterize the entire project.

The Players: Obsession and Succession

William Lambton emerged from relative obscurity to propose this ambitious project. A British infantry officer serving in India, he had developed an interest in surveying and geodesy—the science of measuring the Earth’s shape and size. Historical accounts vary on his exact motivations, but he appears to have been genuinely interested in the scientific challenge. In 1802, he submitted a proposal to the East India Company to conduct a trigonometrical survey beginning in southern India. The Company, recognizing the potential military and administrative value, approved the project and provided Lambton with funding and equipment.

Lambton’s approach was methodical and uncompromising. He began by measuring a baseline near Madras with extraordinary care, using specially calibrated chains and repeatedly checking measurements to eliminate errors. This baseline—a precisely measured straight line on flat ground—would serve as the foundation for all subsequent triangulation. From the endpoints of this baseline, he would measure angles to distant points, using trigonometry to calculate their positions without having to physically measure the distances. These points would form new triangles, extending the network outward like a mathematical spiderweb across the landscape.

The work was grueling beyond anything Lambton’s contemporaries in European surveying had experienced. Observation stations had to be established on hilltops, requiring the construction of tall platforms or towers to elevate the instruments above intervening terrain. In flat country where no hills existed, bamboo towers reaching sixty or even a hundred feet high had to be constructed. The heavy theodolite and other equipment had to be transported to each station, often requiring teams of laborers to carry the instruments through jungle or up mountainsides. At each station, measurements had to be taken under optimal atmospheric conditions—clear air, minimal heat shimmer—which meant waiting for the right weather, sometimes for days or weeks.

Lambton drove himself and his teams relentlessly. He understood that the accuracy of the entire survey depended on minimizing errors at every stage. A small mistake in angle measurement would propagate through the triangulation network, growing larger with each new triangle. He personally checked calculations and re-measured angles when results seemed inconsistent. The work consumed him, and he expected similar dedication from his subordinates. The physical toll was severe—chronic exposure to sun and heat, diseases, exhaustion—but Lambton continued, year after year, watching the triangulation network grow northward across the Indian peninsula.

George Everest joined the survey in 1818 and eventually succeeded Lambton as superintendent. Where Lambton had been the visionary founder, Everest became the methodical perfectionist who would expand and systematize the work. Everest brought a more rigorous mathematical approach, introducing corrections for various sources of error that Lambton had not fully accounted for. He insisted on even more precise instruments and more careful procedures. Under his leadership, the Survey of India—as it had become known—became the official responsibility of the colonial government rather than just a Company project.

Everest’s tenure saw the survey extend into northern India and begin approaching the Himalayas. The challenges multiplied with the scale. The distances grew larger, requiring even more precise angle measurements. The terrain became more difficult. Political complications arose as the survey entered territories that were contested or only nominally under British control. Everest, like Lambton before him, suffered repeated bouts of illness but refused to abandon the work. His name would eventually become immortalized, though not through his surveying achievements directly, but through the practice of naming the world’s highest peak after him—a decision made after his retirement, one he apparently neither sought nor particularly welcomed.

Andrew Scott Waugh succeeded Everest and led the survey into its most dramatic phase: the measurement of the Himalayan peaks. It was during Waugh’s leadership that the calculations identifying Peak XV as the world’s highest mountain were completed. James Walker then took over in 1861, overseeing the survey through its final decade. Walker’s task was to complete the remaining sections, fill in gaps, and ensure the vast triangulation network was properly connected and verified. Under his leadership, the project that Lambton had begun in 1802 finally reached its conclusion in 1871.

Rising Tension: Confronting the Impossible

As the triangulation network extended northward through the 1820s and 1830s, the surveyors confronted increasingly daunting obstacles. The Deccan plateau presented its own challenges, but these paled compared to what lay ahead. The survey required sight lines stretching dozens of miles, which meant finding or creating observation points high enough to see over intervening terrain. In the relatively flat coastal regions, this had been difficult enough. In the varied topography of central India, it became a constant struggle.

The human cost mounted steadily. Survey teams worked in regions where malaria was endemic, where cholera could sweep through a camp in days, where heat stroke felled men regularly. The Indian assistants and laborers who formed the majority of the survey teams suffered the highest casualty rates, though their deaths were rarely recorded with the same detail as those of European officers. They carried the heavy equipment, built the observation towers, cleared sight lines through jungle, and maintained the supply lines that kept the survey moving forward. Without their labor and knowledge of local conditions, the survey would have been impossible, yet history has preserved few of their names.

The technical challenges grew as well. Measuring angles accurately depends on having clear sight lines and stable atmospheric conditions. In India’s heat, air turbulence and heat shimmer could make distant objects appear to waver and shift, introducing errors into angle measurements. The surveyors learned to work in the early morning and evening when atmospheric conditions were most stable. They developed techniques for averaging multiple measurements and for recognizing when conditions made accurate work impossible. But this meant that progress could be maddeningly slow, with days or weeks spent waiting for a few hours of usable observation time.

Towers Reaching Toward Heaven

The bamboo observation towers became symbols of the survey’s ambition and its absurdity. In regions without natural elevation, towers had to be built that could raise instruments and observers high enough to see over obstacles. Some of these structures reached extraordinary heights—contemporary accounts describe towers of sixty, eighty, even a hundred feet or more. Building such structures required engineering skill and enormous labor. Bamboo had to be sourced, transported, and assembled into frameworks stable enough to support not just the weight of instruments and observers, but also to remain steady despite wind.

These towers were dangerous. They swayed in wind, making precise measurements difficult or impossible. They occasionally collapsed, with fatal results. Working at the top of a bamboo tower in fierce heat, trying to make minute adjustments to a theodolite while the entire structure shifted underfoot, demanded extraordinary concentration and nerve. Yet the measurements had to be made. The triangulation network could not advance without them.

The towers also became objects of curiosity and sometimes fear among local populations. Villagers who had never seen such structures wondered at their purpose. Some saw them as religious objects, others as instruments of colonial control—which, in a sense, they were. The survey teams had to negotiate with local authorities for permission to build, for access to land, for labor and supplies. These negotiations could be straightforward or complex, depending on the political situation and local attitudes toward British authority.

The Calculation Challenge

Back at survey headquarters, teams of calculators worked through the mathematics required to transform angle measurements into coordinates and distances. This was computationally intensive work by 19th-century standards. Each triangle in the network required trigonometric calculations to determine the positions of its vertices. These calculations had to account for the curvature of the Earth, for the survey’s reference ellipsoid (the mathematical model of Earth’s shape), for corrections due to elevation, and for various systematic errors in the instruments.

The calculators—many of them Indian mathematicians trained specifically for this work—performed these calculations by hand, using logarithm tables and mechanical aids like slide rules. A single triangle might require hours of calculation, and the network eventually contained thousands of triangles. The potential for arithmetic errors was enormous, so calculations were often performed independently by multiple computers (as these human calculators were called) and then compared. Discrepancies had to be resolved, which might require returning to the field to re-measure.

The Survey of India developed increasingly sophisticated mathematical methods for adjusting the network. When triangulation chains closed on themselves—when survey lines that had taken different paths met again—there were inevitably small discrepancies. These had to be distributed through the network in a way that minimized overall error. This was a problem in what would now be called optimization, and 19th-century surveyors developed practical solutions that foreshadowed modern statistical approaches.

Political Complications

The survey operated within the complex political landscape of British India. Some regions were under direct British control, administered by the Company or later by the colonial government. Others were princely states with varying degrees of autonomy. Still others were contested territories where British authority was disputed or nominal. Conducting a survey in such regions required diplomatic skill as much as technical expertise.

Some rulers welcomed the survey, seeing it as a sign of British favor or modernization. Others viewed it with suspicion, correctly perceiving it as an instrument of imperial control. Accurate maps facilitated military operations, tax assessment, and economic exploitation. Knowledge of a territory’s geography gave military advantages. Allowing the British to survey your domain was, in effect, making yourself more vulnerable to their power.

There were regions the survey could not safely enter, areas where British survey teams would have faced active resistance. In such cases, the surveyors had to work around these gaps, extending their triangulation network around or over them, planning to fill them in later when political conditions changed—as they usually did, through British military conquest or diplomatic pressure.

The Turning Point: Discovering the Roof of the World

As the triangulation network extended into northern India in the 1840s, the surveyors encountered a new challenge of an entirely different magnitude: the Himalayas. These mountain ranges were known to be high, but no one knew exactly how high. European travelers and geographers had speculated, with estimates varying wildly. Some thought Chimborazo in South America might be higher. Others believed certain Andean peaks exceeded anything in Asia. No one could be certain because no one had measured with precision.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey would change that. As observation stations moved closer to the Himalayas, surveyors could begin measuring angles to the major peaks. The distances were enormous—sometimes over a hundred miles from the observation station to the mountain—but the principles of triangulation still applied. By measuring angles from multiple stations whose positions had been precisely determined through the triangulation network, the surveyors could calculate the positions and elevations of the peaks.

The work required extraordinary precision. At distances of a hundred miles or more, a tiny error in angle measurement could translate to massive errors in calculated elevation. Atmospheric refraction—the bending of light as it passed through layers of air at different temperatures and densities—had to be carefully corrected for. The curvature of the Earth became a significant factor. Every source of error had to be identified and minimized.

The calculations were performed by the survey’s team of mathematicians and calculators, working with the angle measurements sent back from the field. One peak in particular began to stand out in the data. Designated Peak XV (the survey used numerical designations before attempting to determine local names), this mountain consistently showed extreme elevation in calculations from multiple observation stations. Initial calculations were treated with skepticism—such extraordinary height seemed improbable. But as more measurements came in, all pointing to the same conclusion, the surveyors became convinced they had found something remarkable.

The detailed calculations took years. Multiple observers measured angles to Peak XV from several different locations. The mathematics required careful treatment of all corrections and error sources. The computers checked and rechecked their work, aware that claiming to have found the world’s highest mountain would invite scrutiny. But the numbers kept returning the same answer: Peak XV stood higher than any previously measured mountain on Earth.

Andrew Scott Waugh, who led the survey during this period, eventually announced the discovery. The exact date of the final confirmation is debated by historians, but it occurred during Waugh’s tenure after Everest’s retirement. Waugh made the decision to name the peak after his predecessor, George Everest, despite Everest’s own objections to the practice of renaming geographic features after surveyors. Everest argued that local names should be preserved, but Waugh insisted, claiming that the mountain’s local name was either unknown or had multiple conflicting versions in different languages.

Thus Peak XV became Mount Everest, a name that would become perhaps the most famous topographic feature on Earth. The survey’s measurements—eventually refined to show the peak at 29,002 feet, remarkably close to modern measurements using satellite technology—were initially met with some skepticism in Europe but eventually accepted. The Great Trigonometrical Survey had not only mapped India but had also rewritten geography, identifying the planet’s highest point.

This discovery transformed the survey from a technical project of primarily imperial interest into something that captured global imagination. The idea of measuring the tallest mountain on Earth through mathematical calculation, without climbing it or even approaching its base closely, demonstrated the power of systematic scientific methods. It showed that the British Empire commanded not just military force but also technical expertise and scientific sophistication.

Yet the discovery was also, in many ways, a product of the entire survey’s accumulated work. The heights of the Himalayan peaks could only be determined accurately because the triangulation network extending from southern India to the mountains’ foothills had been measured with such care. The position and elevation of each observation station used to measure Everest had been determined through chains of triangulation stretching back to Lambton’s original baseline measured on the Madras plains four decades earlier. Any accumulated errors through all those thousands of triangles would have compromised the final calculation. The fact that the measurement was accurate validated not just the Himalayan observations but the entire methodological approach Lambton had pioneered and his successors had perfected.

Aftermath: A Map and Its Meanings

The Great Trigonometrical Survey officially concluded in 1871 under James Walker’s leadership. After sixty-nine years of continuous work, the project had achieved its primary goal: India was now the most precisely mapped territory on Earth. The triangulation network covered the subcontinent from the southern tip to the Himalayan peaks, from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal. The positions of thousands of points had been determined with unprecedented accuracy. Elevations had been calculated. The shapes of coastlines, rivers, and mountain ranges had been captured with mathematical precision.

The practical outputs were impressive. Detailed topographic maps at various scales could now be produced, all referenced to a consistent coordinate system. These maps served countless purposes. Military planners could design campaigns with accurate knowledge of distances, terrain, and logistics. Civil administrators could assess land holdings for taxation. Engineers could plan roads, railways, and irrigation projects. Geologists could map mineral deposits. Botanists and zoologists could document the distribution of species. The survey’s data became foundational for virtually all subsequent scientific and administrative work in India.

The Survey of India itself continued as an institution, maintaining and extending the network, conducting more detailed regional surveys, and producing updated maps. The methods pioneered during the Great Trigonometrical Survey—the careful triangulation, the rigorous error correction, the systematic approach to large-scale mapping—became models for surveying projects worldwide. The British would apply similar methods in other colonial territories. Other nations would adopt the techniques for their own surveys.

Yet the survey’s completion also marked a closing of a particular era. The men who had dedicated their lives to the project—those who survived it—could finally rest. The toll had been severe. Lambton himself had died during the survey’s course, working until the end. Everest survived but suffered lifelong health problems attributed to his years in India. Countless Indian assistants, calculators, and laborers had given years or lives to the work. The exact number who died during the survey’s seven decades is unknown, as records were not consistently kept for Indian workers, but tropical diseases, accidents, and the sheer physical demands of the work claimed many victims.

The survey had also been enormously expensive. The East India Company and later the British colonial government had poured resources into the project continuously for nearly seven decades. The sophisticated instruments, the personnel costs, the logistics of maintaining survey teams across a subcontinent—all of this required sustained funding that few other scientific projects could claim. The investment reflected the survey’s strategic importance to imperial control, but it also represented a massive commitment to a long-term scientific endeavor.

Legacy: Measuring Empire, Measuring Knowledge

The Great Trigonometrical Survey’s legacy extends far beyond its immediate practical outputs. It represents one of the most ambitious applications of Enlightenment rationality to the physical world, an attempt to capture an entire subcontinent in numbers and coordinates. The survey demonstrated that systematic application of scientific methods could overcome seemingly impossible challenges of scale and complexity. It showed that mathematical precision could be achieved even in the most difficult conditions through careful methodology and relentless attention to detail.

The survey also embodied the relationship between science and empire. It was simultaneously a scientific achievement and an instrument of colonial control. The knowledge it produced served both intellectual curiosity and imperial domination. This dual nature raises questions about the relationship between knowledge and power that remain relevant. Can we separate the scientific value of the survey from its role in facilitating colonialism? Should we? These questions have no simple answers, but they remind us that science never exists in a political vacuum.

The identification of Mount Everest as the world’s highest peak had its own profound legacy. It transformed the mountain from a distant, barely-known feature into an object of global fascination. The name “Everest”—a British imposition replacing or ignoring local names—itself reflects the cultural imperialism of the era. Yet the mountain’s status as Earth’s highest point made it a magnet for explorers and adventurers, eventually leading to decades of mountaineering attempts and the eventual first ascent in 1953. The survey’s mathematical calculation preceded by nearly a century any human’s direct experience of the summit.

The methodological innovations of the survey influenced surveying and geodesy worldwide. The techniques for error correction, network adjustment, and systematic triangulation became standard practices. The survey demonstrated that even with 19th-century technology, extraordinary precision was achievable through careful methodology. Modern surveying, while using vastly superior technology like GPS satellites and laser ranging, still builds on principles that the Great Trigonometrical Survey helped establish.

The survey’s data remained valuable for over a century. The positions and elevations determined in the 19th century served as reference points well into the 20th century. Modern surveyors, when re-measuring parts of India with contemporary equipment, have found that the old survey’s results were remarkably accurate, with errors often measuring only feet across distances of hundreds of miles. This accuracy validated the extraordinary care taken by Lambton, Everest, Waugh, Walker, and their teams.

The institutional legacy persists as well. The Survey of India, which became the formal organization conducting the work under Everest’s leadership, continues to exist today as an agency of the Government of India. It remains responsible for surveying, mapping, and maintaining geodetic control for the nation. The traditions and standards established during the Great Trigonometrical Survey influenced the organization’s culture and methods for generations.

What History Forgets: The Human Cost and the Invisible Workers

Standard accounts of the Great Trigonometrical Survey typically focus on the British officers who led it—Lambton, Everest, Waugh, Walker—and on the dramatic discovery of Mount Everest. These accounts often present the survey as a triumph of British engineering and scientific skill, a demonstration of the benefits of rational methods and disciplined organization. What such accounts frequently minimize or omit entirely is the immense contribution of Indian workers and the severe human cost the project exacted.

The survey teams that actually carried out the measurements, built the observation towers, transported equipment across impossible terrain, and performed the endless calculations were predominantly Indian. They included surveyors, calculators (many highly skilled mathematicians), instrument makers, laborers, and guides. Their knowledge of local languages, customs, and geography was essential. Local workers knew which routes were passable, which water sources were reliable, which seasons made travel feasible. Calculators trained in Indian mathematical traditions performed the intricate trigonometric computations required to transform angle measurements into coordinates.

Yet the historical record preserves little about these individuals. Official reports mention them as generic categories—“native assistants,” “computers,” “laborers”—rather than as named individuals with their own stories. When the survey celebrated its achievements, the accolades went to the British officers. When positions of authority were filled, Indians were systematically excluded from senior roles regardless of their competence. This reflected the racial hierarchies of British colonialism, which assumed European superiority even in technical matters where Indian workers often possessed equal or superior skills.

The mortality rate among survey workers, particularly Indian laborers, was almost certainly higher than among British officers, though exact figures are difficult to determine due to incomplete record-keeping. Diseases like malaria, cholera, and typhoid struck everyone, but Indian workers often had less access to medical care and were expected to continue working under conditions that would have prompted British officers to rest. Accidents during tower construction or equipment transport killed or injured many. The names of most of these casualties were never recorded.

Some historical accounts describe the survey as having taken place in a scientifically neutral space, as if the measurement of angles and distances existed apart from the political context of colonial rule. But the survey was never politically neutral. It operated with military protection in contested regions. It benefited from the authority of the colonial state to requisition land, labor, and supplies. Its results served military and administrative purposes that facilitated British control. Local populations sometimes resisted, not from ignorance or superstition as colonial accounts often suggested, but from entirely rational recognition that the survey served their colonizers’ interests.

The environmental impact of the survey, though small by modern standards, was also real. Forests were cleared to create sight lines between observation stations. Hilltops were leveled or modified to create stable platforms for instruments. Local ecosystems were disturbed by the passage of large survey teams. These impacts were considered irrelevant at the time, barely worth mentioning, but they represent another dimension of the survey’s effects that standard histories neglect.

There is also the question of knowledge displaced or devalued by the survey. India possessed indigenous traditions of geography, cartography, and spatial knowledge developed over centuries. Local communities knew their territories intimately, with rich vocabularies for terrain features and sophisticated wayfinding systems. The survey generally dismissed or ignored this knowledge, assuming that only European mathematical methods could produce true understanding. In replacing local maps and geographic knowledge with standardized British survey maps, something was lost—not accuracy in the narrow sense, but richness, local meaning, and indigenous ways of understanding landscape.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey was undeniably a remarkable achievement in the history of surveying and geodesy. It demonstrated human capability to measure and map at unprecedented scales. It produced knowledge of lasting scientific value. Yet acknowledging this achievement need not require us to ignore its context and costs. It was a colonial project, conducted by a colonial power for colonial purposes, using both British expertise and Indian labor in a relationship structured by imperial hierarchy. The mathematical precision of its results coexisted with the violence and exploitation of colonial rule.

Understanding the survey fully requires holding these contradictions in mind: brilliant scientific work conducted for troubling purposes; remarkable technical achievement built on unacknowledged labor; mathematical precision used to facilitate political domination; knowledge creation intertwined with knowledge destruction. The survey measured India with extraordinary accuracy while fundamentally misunderstanding it in other ways, seeing it primarily as territory to be controlled rather than as a place where people lived complex lives largely indifferent to British imperial ambitions.

The survey’s maps presented India as a known, measured, controlled space. But maps can never capture the full reality of lived experience in a place. The India that existed in the survey’s triangulation networks and elevation tables was not the India experienced by the millions who actually lived there, who knew their villages and regions through memory, story, and daily practice rather than through coordinates and contour lines. Both forms of knowledge were real, but they served different purposes and reflected different relationships to the land. The survey’s triumph was also, in its way, a transformation and a loss—the reduction of a vast, complex human and natural landscape to the precise but limited language of mathematical measurement.