Shivaji’s Great Escape: The Fruit Basket Gambit That Defied an Empire

The fruit baskets left the mansion every evening just after sunset prayers. Large woven containers, each requiring two men to carry, filled with mangoes, pomegranates, melons—gifts of devotion sent to Brahmins and holy men throughout Agra. The Mughal guards had grown accustomed to the sight. The Maratha chieftain, they whispered among themselves, was trying to buy spiritual merit, perhaps sensing that his time was running short. They checked each basket going into the mansion with meticulous care—Aurangzeb’s orders were explicit about what could reach the prisoner. But the baskets going out? Those were offerings to holy men. To search them would be sacrilege, an insult to the Brahmins, a violation of dharma that even Emperor Aurangzeb’s guards dared not risk.

Inside the mansion on that fateful evening in August 1666, Shivaji Bhonsale—warrior, strategist, and king in all but formal title—was counting on exactly that reluctance. The man who had carved a kingdom from the contested territories between the Sultanate of Bijapur and the Mughal Empire, who had captured forts considered impregnable and evaded armies sent to destroy him, now faced perhaps his greatest challenge: escaping from the very heart of Mughal power. Not through battle or siege, but through cunning, patience, and an intimate understanding of the cultural forces that bound even an emperor’s hands.

The evening call to prayer echoed across Agra as the first basket was carried out. Inside, curled in a space that seemed impossibly small for a grown man, Shivaji controlled his breathing, feeling the sway of the carriers’ steps, hearing the muffled conversation of guards, waiting for the moment when the rhythm would change, when the carriers’ footsteps would quicken, when he would know they had passed beyond the immediate surveillance of Aurangzeb’s watchers.

This was not how their meeting was supposed to end.

The World Before

The India of 1666 was a subcontinent of contested sovereignty, where the Mughal Empire’s claim to paramount power faced challenges from multiple directions. Aurangzeb, who had seized the throne from his father Shah Jahan through a brutal war of succession, ruled an empire that stretched from Afghanistan to Bengal, from the Himalayas into the Deccan plateau. Yet the farther his authority extended from the imperial heartland, the more it frayed into negotiation, alliance, and the constant dance of power between the center and ambitious regional leaders.

The Deccan—that vast plateau that formed central India’s elevated heart—was particularly contested terrain. Here, the Mughal Empire pressed southward, seeking to absorb or destroy the Sultanates that had ruled the region for generations. The Sultanate of Bijapur, wealthy from trade and agriculture, clung to independence while playing a careful game of alliance and resistance. And in the Western Ghats, in the hill country and fortresses that commanded the routes between the plateau and the coast, a new power was emerging.

The Maratha people—warriors, farmers, and administrators whose ancestors had served various Deccan rulers—were coalescing into a political force under leaders who understood both the military and administrative arts. The Bhonsle family, retainers who had served Bijapur, had been granted jagirs—land grants with rights to collect revenue and maintain military forces. From this foundation, using intimate knowledge of the Western Ghats’ terrain and the loyalty of local populations, a challenge to both Bijapur and Mughal authority was taking shape.

Into this world of shifting allegiances and constant military maneuvering, Shivaji Bhonsale had been born in 1630 at Shivneri Fort, inheriting his jagir from his father Shahaji, himself a notable military commander. Raised by his mother Jijabai while his father served in distant campaigns, Shivaji had grown up hearing tales of ancient Hindu kings, of dharma and righteous rule, of the warrior’s duty to protect the people and uphold justice. These were not merely stories but a political education, a vision of what leadership could mean in an age of imperial expansion and religious conflict.

By the 1660s, Shivaji had transformed his inherited jagir into something approaching a kingdom. He had captured forts through brilliant strategy—sometimes through direct assault, sometimes through infiltration, often through negotiations that turned his enemies’ retainers into his allies. He had created an administrative system that collected revenue efficiently while earning the loyalty of farmers and merchants. He had raided Mughal territories, most famously the port of Surat in 1664, demonstrating that Aurangzeb’s authority was not absolute even in territories the empire claimed to control.

This success made Shivaji simultaneously valuable and dangerous in the calculations of greater powers. To the Mughals, he was an upstart who needed to be either controlled or destroyed. To Bijapur, he was a former retainer who had exceeded his authority, yet whose military skills might be useful. To the populations of the Deccan, increasingly, he represented an alternative—a Hindu ruler in an age of Muslim sultanates and empires, a local power who understood their needs and spoke their languages.

The question by 1666 was not whether Shivaji mattered—clearly he did—but what would become of this emerging power. Would he be absorbed into the Mughal system, becoming one more mansabdar, a rank-holder in the empire’s elaborate hierarchy? Would he continue his independent path, building toward sovereignty? Or would he overreach and be destroyed, his nascent kingdom scattered, his forts reclaimed, his name becoming merely another footnote in the Deccan’s long history of rebellion and conquest?

The answer would depend on decisions made in Agra, in Aurangzeb’s court, where power was measured not just in military force but in honor, precedent, and the intricate protocols that governed how an emperor treated with those who came before him—whether as subjects, as allies, or as equals.

The Players

Shivaji Bhonsale in 1666 was thirty-six years old, at the height of his physical powers and military reputation. Those who met him noted his relatively modest appearance—he was not tall, not physically imposing in the manner of some warrior-kings. His strength lay in his mind, in eyes that observers described as constantly assessing, calculating, seeing patterns and possibilities that others missed. He dressed simply compared to the elaborate fashions of Mughal nobles, preferring functional military attire even in formal situations—a choice that was itself a political statement about the source of his authority.

His upbringing under Jijabai’s guidance had given him a strong grounding in Hindu tradition and Sanskrit learning, unusual for a military commander of his era. He could quote from the Mahabharata and Ramayana, drawing lessons about dharma and righteous rule. Yet he was also deeply pragmatic, willing to employ Muslim soldiers and administrators, to negotiate with Sultanates, to use any tool or alliance that served his strategic goals. This combination of religious conviction and political flexibility made him difficult for opponents to predict or categorize.

He had multiple wives, as was customary for rulers of his standing—Saibai, Soyarabai, Putalabai, and Sakavaarbai are recorded—and children including his eldest son who accompanied him to Agra. His household was organized with careful attention to loyalty and capability, with trusted retainers managing different aspects of his growing administration. He inspired deep devotion among his followers, built through shared hardship in military campaigns, through fair treatment and reward for service, and through the sense that they were part of something larger than mere conquest—the building of a kingdom.

By contrast, Aurangzeb at forty-eight was the ruler of the world’s most powerful empire, a man who had fought three brothers and deposed his father to claim the throne. Where Shivaji was known for religious tolerance despite his Hindu identity, Aurangzeb was increasingly identified with orthodox Islamic policy, demolishing some temples, imposing the jizya tax on non-Muslims, and seeing his rule as having a religious dimension that transcended mere political authority.

Aurangzeb was in many ways the opposite of Shivaji in personality—austere where Shivaji was reportedly warm with his followers, rigid in protocol where Shivaji was flexible in tactics, convinced of the rightness of imperial hierarchy where Shivaji believed in earned authority. The emperor was also brilliant in his own way—a capable military commander who had won his throne through superior generalship, an administrator who worked long hours on the details of governance, a man of personal piety who lived simply despite the wealth at his disposal.

Yet Aurangzeb’s strengths created their own weaknesses. His insistence on proper hierarchy and protocol meant he could not easily adapt when someone like Shivaji refused to fit into expected categories. His religious orthodoxy, which he saw as righteous, alienated many of his Hindu subjects and officials, creating the very resistance he sought to overcome. His focus on the Deccan campaigns, which would consume the latter half of his reign, pulled resources away from other frontiers and created opportunities for new challenges to Mughal authority.

The confrontation between these two men—one building power upward from local foundations, the other wielding authority downward from imperial command—was in many ways inevitable. Tradition holds that Aurangzeb sent an invitation to Shivaji to attend the Mughal court, possibly with assurances of honor and recognition. Whether this was genuine diplomatic outreach or a trap designed to neutralize a troublesome opponent remains debated by historians. What is certain is that Shivaji, calculating the risks and potential benefits, decided to go.

The journey to Agra was itself a statement—a Maratha leader traveling deep into Mughal territory, to the empire’s capital, to meet the emperor. Shivaji brought his son and a modest retinue, not the large force that would have signaled military intentions but enough attendants to mark his status as an independent leader rather than a mere subordinate. The journey took weeks, passing through territories where Mughal authority was unquestioned, where the local populations looked upon the Maratha party with curiosity and perhaps unease.

When they arrived in Agra, that great Mughal capital with its massive fort, its bustling bazaars, its population accustomed to seeing the powerful come and go, Shivaji entered a world built to demonstrate imperial majesty. Everything about Agra—from the scale of its monuments to the elaborate protocols of its court—was designed to make visitors understand their place in a hierarchy that put the emperor at the apex, with all others ranging below according to their rank, their service, and the emperor’s pleasure.

What Shivaji expected from this meeting and what he received would create the crisis that led to his desperate escape.

Rising Tension

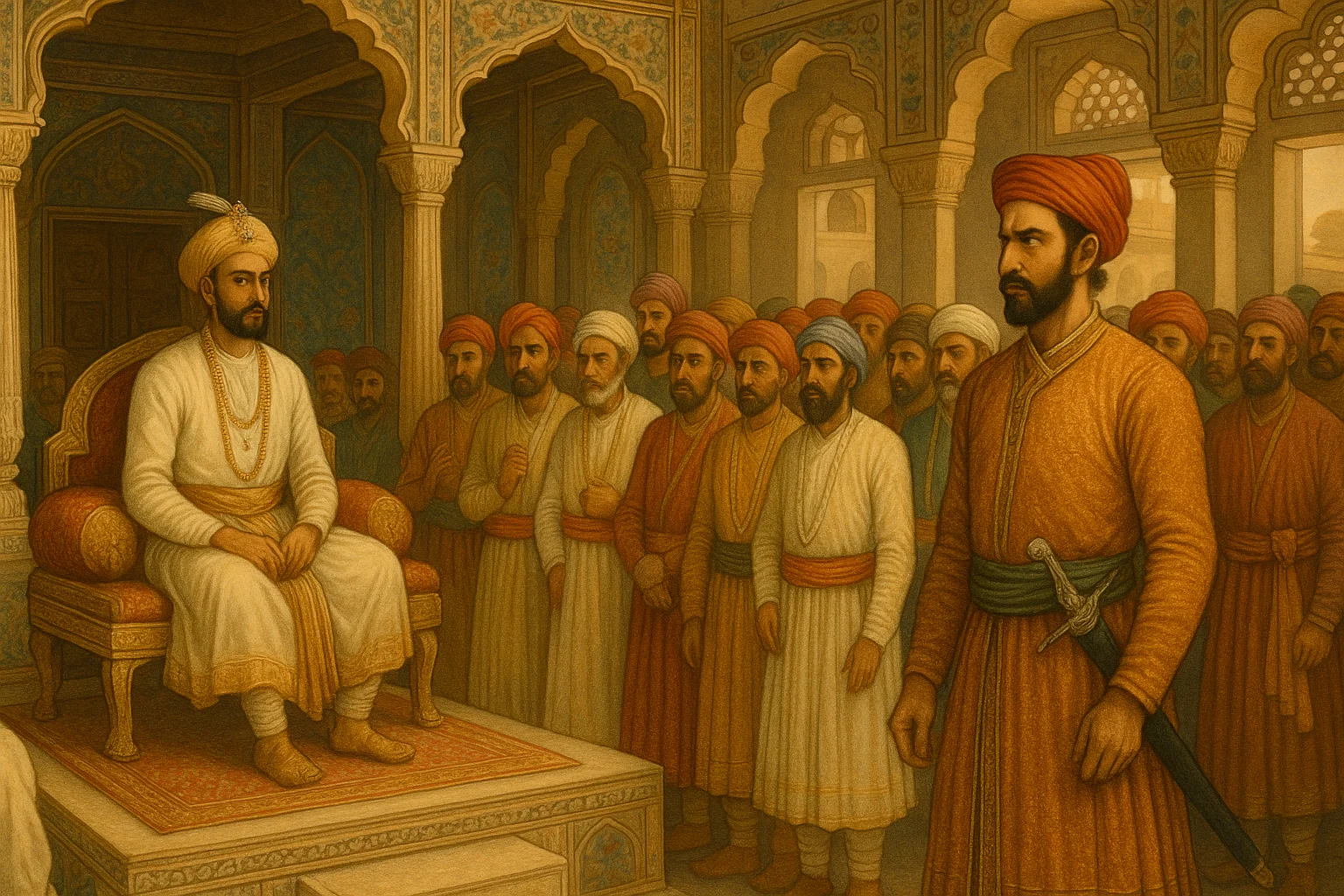

The durbar—the formal court audience—where Shivaji was to be presented to Aurangzeb was held according to the strict protocols that governed such occasions. The Mughal court was theater as much as governance, a carefully choreographed display where position in the hall, distance from the throne, the manner of greeting, and the gifts exchanged all carried precise meanings understood by those versed in the system.

Historical accounts, though they vary in details, agree on the essential crisis: Shivaji felt he was not given the honor due to an independent ruler but was instead treated as a subordinate mansabdar, a rank-holder within the Mughal system. The exact nature of the slight is debated—whether it was his position in the hall, the rank he was assigned, or the manner in which Aurangzeb received him—but the effect was clear. Shivaji considered himself insulted.

In the court, tradition holds, he expressed his displeasure. For Aurangzeb, this was likely incomprehensible insubordination—a regional leader who had been granted an audience with the emperor was complaining about the honor shown to him? The emperor’s view of hierarchy was clear: he was the Padishah, the King of Kings, and all others held their authority by his leave or existed in rebellion against rightful order. To show dissatisfaction with the emperor’s judgment was not merely rude but a fundamental challenge to the structure of authority.

The aftermath was swift. Shivaji was not arrested in the formal sense—such treatment of someone who had come to court on imperial invitation would have created dangerous precedents, suggesting that the emperor’s safe-conduct could not be trusted. Instead, he was effectively placed under house arrest, confined to a mansion in Agra with guards posted ostensibly for his “protection” but actually to ensure he could not leave. His movements were restricted, his communications monitored, his retinue prevented from operating freely.

For Shivaji, the situation was immediately dire. He was deep in enemy territory, hundreds of miles from his forts and loyal forces. If Aurangzeb decided to eliminate him, there would be little he could do through direct action. An escape attempt that failed would give the emperor justification to treat him as a criminal rather than a guest. Yet remaining meant accepting whatever fate Aurangzeb chose to impose—perhaps permanent detention, perhaps forced submission on humiliating terms, perhaps eventually a quiet execution that would be explained as illness or accident.

The Mansion Prison

The mansion where Shivaji was confined was comfortable in physical terms—this was no dungeon but a residence suitable for a noble. Yet its comfort made it more effective as a prison. The guards were not jailers but imperial soldiers who treated the Maratha leader with formal respect while ensuring he went nowhere without their knowledge. The mansion’s walls were not particularly high or strong, but they didn’t need to be—Shivaji could no more fight his way out of Agra than he could fly.

In this confined space, Shivaji began to plan. His genius had always been strategic rather than tactical—seeing the larger patterns, understanding what motivated his opponents, finding the approaches others overlooked. Now he applied this mind to his own predicament. Direct escape was impossible. Negotiations seemed to lead nowhere—Aurangzeb had made his decision about Shivaji’s status, and the emperor was not known for reversing his judgments. Fighting was futile. That left cunning.

He began to plead illness. Historical accounts describe him taking to his bed, complaining of various ailments, receiving physicians. Whether he was actually sick or feigning is unclear—he may have deliberately made himself ill through fasting or other means, or he may have simply been an excellent actor. The effect was to make his captors believe he was declining, no longer a threat, perhaps dying.

Simultaneously, he began a practice of sending gifts to Brahmins and holy men throughout Agra. This was presented as the action of a pious man seeking spiritual merit, perhaps preparing for death. Large baskets of fruit and sweets were assembled daily and sent out as offerings. The Mughal guards, watching for weapons or messages being smuggled in, paid little attention to these departures. Religious offerings were common practice, and to interfere with them would have been culturally problematic.

The Plan Takes Shape

Inside the mansion, Shivaji was conducting a careful experiment. The baskets that left each evening were large—it took two strong men to carry each one. They were woven from materials that would not support close inspection of their contents without unpacking everything. They left regularly, establishing a pattern. And crucially, the guards who watched them depart did so with declining attention—routine breeds inattention, and religious offerings seemed the least threatening of activities.

Shivaji observed the timing of guard changes, the patterns of surveillance, the moments when attention was lowest. He noted which guards were most diligent and which had grown bored with watching a sick man’s household. He saw that while the mansion’s entrance was closely watched, the servants’ areas where the baskets were prepared and loaded received less scrutiny. Most importantly, he understood that the guards were looking for someone trying to sneak out, not for someone hiding in plain sight among the regular traffic of gifts.

The decision to escape would require perfect timing. If Shivaji disappeared and immediate pursuit was raised, he would be caught before he could get far from Agra. He needed not just to leave the mansion but to create enough confusion or delay that he could gain substantial distance before the alarm was raised. This meant his departure had to seem routine until well after he was gone.

According to tradition, Shivaji shared his plan with his son and a few absolutely trusted attendants. His son would remain behind—both as a hostage to ensure the household’s good behavior and to maintain the fiction that Shivaji was still present. The attendants would continue the routine of preparing baskets, of sending them out, of tending to the “invalid” in his chambers. For days, perhaps weeks after Shivaji’s escape, the household would need to maintain the appearance that nothing had changed.

The risks were extraordinary. If discovered in the attempt, Shivaji would have confessed his intention to escape, giving Aurangzeb justification for harsh treatment. If caught shortly after leaving, he would be brought back in humiliation, his reputation for cleverness destroyed. If his son or attendants were tortured for information—a real possibility once the escape was discovered—the truth would emerge quickly. Every element had to work perfectly.

The Turning Point

The evening chosen for the escape was, by necessity, one that seemed like any other. The baskets were prepared as usual, filled with fruits and sweets, covered with cloths appropriate for religious offerings. The carriers who would bear them were either trusted retainers or men who had been convinced to look the other way at the right moment—tradition holds that Shivaji’s agents had carefully prepared this network, though the exact details are lost to history.

As sunset prayers echoed across Agra, as the light faded into the brief tropical twilight, the first baskets were carried out. The guards conducted their usual cursory inspection—a glance inside, a check that the carriers were recognized members of the household. The baskets passed through, bound for various Brahmins and religious establishments across the city. It was a scene that had been repeated so many times that it had become invisible through familiarity.

Inside one of these baskets, Shivaji had folded himself into a space that seemed impossibly confined. The posture required—knees drawn up, head bent, every muscle held tight to minimize his profile—must have been agonizing. The basket’s weave allowed some air but limited visibility to fragments and shadows. The weight of fruit surrounding him created pressure on all sides. The swaying motion as the carriers walked would have been disorienting, making it difficult to track their progress or maintain balance.

The critical moment came at the mansion’s gate, where the guard force was strongest. Here, the carriers paused while guards exchanged words with them—routine questions about destinations, perhaps casual conversation. Through the basket’s weave, Shivaji would have seen the flicker of torchlight, heard the guards’ voices. Any unusual behavior by the carriers, any sign of nervousness, could have prompted closer inspection. But the moment passed. The baskets were waved through.

Once beyond the immediate mansion perimeter, the carriers’ pace changed. Whether following a predetermined route or responding to Shivaji’s whispered instructions, they moved through Agra’s evening streets toward a destination where horses and trusted men waited. The journey through the city—how long it took, exactly what route was followed—is not precisely recorded in surviving accounts. But tradition holds that Shivaji remained hidden until he was well beyond the areas of heaviest Mughal military presence.

When he finally emerged from the basket, at some safe house or quiet location outside the city’s center, Shivaji was no longer a prisoner but a fugitive. Now began the second phase of the escape—not just leaving the mansion but crossing the hundreds of miles back to Maratha territory while Mughal forces hunted for him.

The Flight to Safety

Historical accounts provide limited detail about Shivaji’s journey from Agra back to his homeland in the Western Ghats. The distance was immense—roughly 800 miles through territory where Mughal authority was strong. He could not travel openly or with a large retinue. Every town and fort between Agra and the Deccan potentially held Mughal officials who would be ordered to capture him once his escape was discovered.

The route, by necessity, would have avoided main roads and major towns. Tradition holds that Shivaji traveled disguised as a holy man or common traveler, that he relied on a network of supporters and sympathizers who provided shelter and information, that he moved mostly at night when travel was less observed. Whether he traveled alone or with a handful of companions, whether he went directly or followed a circuitous route to evade pursuers—these details have been lost or embellished beyond historical verification.

What is certain is that sometime after Shivaji’s departure from the mansion, his absence was discovered. The household’s attempt to maintain the fiction of his presence could only last so long—eventually, officials would demand to see him, or the routine would break down. When the truth emerged, Aurangzeb’s response was likely swift and furious. The prisoner who had been under his control, who he had thought neutralized, had simply vanished from the heart of the Mughal capital.

Orders would have gone out immediately—to search parties, to forts along possible escape routes, to governors of provinces through which Shivaji might pass. Mughal military and administrative efficiency, normally formidable, was mobilized to recapture the escaped prisoner. Yet by the time these orders reached provincial officials and forces were organized to search key routes, Shivaji had a lead measured in days. In the race between a fugitive with detailed knowledge of the terrain and pursuers operating in unfamiliar territory at the end of long communication lines, distance favored the fugitive.

The exact timeline remains unclear, but tradition holds that Shivaji eventually reached Maratha-controlled territory safely. The man who had entered Agra as an honored guest, who had been reduced to a prisoner, who had escaped in a fruit basket, had completed one of history’s most remarkable journeys—not a military campaign or a political negotiation, but a personal trial of will, planning, and endurance.

Aftermath

News of Shivaji’s escape would have sent complex messages throughout the political world of 17th century India. For the Marathas and Shivaji’s supporters, it was a propaganda victory of immense proportions. Their leader had been captured by the greatest empire in India, held in its capital, and had still escaped through cleverness and courage. The story would be repeated and embellished, becoming evidence of Shivaji’s special qualities, perhaps even divine protection.

For Aurangzeb and the Mughal administration, it was an embarrassing failure that raised uncomfortable questions. How had a prisoner escaped from the capital itself? Who had helped him? Had guards been bribed or negligent? The emperor’s reputation for control and authority had been damaged. More practically, Shivaji was now back in the Deccan, likely more hostile to Mughal authority than before, his prestige enhanced rather than diminished by his Agra experience.

The immediate aftermath saw renewed conflict in the Deccan. Shivaji, rather than being chastened by his near-disaster at Agra, seems to have been energized. He resumed military operations, capturing more forts, expanding his administration, and consolidating power. The Mughals continued their efforts to control or destroy him, but with the knowledge that conventional approaches—military force, negotiation, even capture—had all proven insufficient against this particular opponent.

For Shivaji’s son and the attendants left behind in Agra, the consequences were likely severe in the immediate term. Aurangzeb could not punish Shivaji directly, but those who had remained could face the emperor’s displeasure. Historical accounts vary on their ultimate fate—some suggest they were eventually released through negotiations, others that they remained prisoners for extended periods. The exact truth is unclear, but their sacrifice enabled Shivaji’s escape.

The escape from Agra became a defining moment in Shivaji’s life narrative, one of the stories that established his legendary status. But it was not the culmination of his career—rather, it marked a transition. Before Agra, he had been a successful regional military leader, a thorn in the side of greater powers but not yet clearly something more. After Agra, he moved decisively toward sovereignty.

Legacy

In 1674, eight years after his escape from Agra, Shivaji was formally crowned Chhatrapati—emperor—at Raigad Fort. The ceremony was elaborate, drawing on Hindu tradition and creating new protocols appropriate for a ruler who claimed authority independent of both the Sultanate of Bijapur and the Mughal Empire. The coronation was not merely symbolic but a political declaration: the Maratha kingdom was no longer just a military challenge to other powers but a sovereign state with its own legitimate ruler.

The escape from Agra contributed to making this moment possible. Had Shivaji died or been permanently captured in Aurangzeb’s prison, the Maratha movement would have likely fragmented, with various leaders competing for his legacy but none able to fully claim it. His survival and successful return demonstrated both his personal qualities and the viability of the emerging Maratha state—showing that it had the organization, loyalty, and capability to protect its leader even in dire circumstances.

The coronation at Raigad Fort occurred in territory that Shivaji controlled absolutely, on a mountain fortress that symbolized Maratha power and independence. The contrast with his position at Aurangzeb’s durbar eight years earlier could not have been more stark. Then, he had been one more subordinate seeking recognition from a greater power. Now, he was asserting equality, claiming a sovereignty that derived not from Mughal grant but from his own authority and accomplishments.

Shivaji’s death came in 1680 at Raigad Fort, the very place where he had been crowned. His life work—the transformation of a jagir into a kingdom, the creation of an administrative and military system that could challenge empires, the establishment of Maratha power as a permanent feature of Indian politics—was complete in its essential elements, though its full flowering would come under his successors.

The Maratha Empire that emerged from Shivaji’s foundation would eventually control vast territories across India, bringing Mughal expansion to an end and dominating Indian politics in the 18th century until the British conquest. While later Maratha rulers often differed from Shivaji in style and methods, they all claimed descent from his legacy, both literal and political. The empire he founded continued until 1818, when British forces finally destroyed Maratha power after a series of hard-fought wars.

The escape from Agra became central to how Shivaji was remembered—evidence of his cleverness, his courage, and the special qualities that set him apart from ordinary leaders. In Maratha tradition, in the broader Hindu imagination, and eventually in Indian nationalist narratives, the image of Shivaji hiding in a fruit basket to escape the Mughal emperor became iconic. It represented the triumph of native Indian power over imperial authority, the victory of cunning over brute force, the possibility of resistance against overwhelming odds.

What History Forgets

While the dramatic story of the fruit basket escape has become legendary, certain aspects of the episode are often overlooked in popular retellings. The role of Shivaji’s supporters in Agra—the network that must have existed to make the escape possible—remains largely anonymous. Tradition holds that various individuals helped prepare the escape, maintained the fiction of Shivaji’s presence after his departure, and assisted his journey back to Maratha territory. These people faced real risks, yet their names and stories have been largely lost.

The experience of Shivaji’s son, left behind as what amounted to a hostage, complicates the heroic narrative. His father’s escape meant his own continued captivity, yet sources suggest he neither betrayed the escape plan nor expressed resentment about his situation. The psychological complexity of this position—supporting his father’s escape while knowing it meant his own probable continued imprisonment—speaks to family loyalties and political calculations that don’t fit easily into simplified retellings.

The cultural dimension that made the escape possible—the Mughal guards’ reluctance to closely inspect religious offerings—reflects a complex reality about religious practice in Mughal India. Aurangzeb’s later reputation for religious intolerance has sometimes overshadowed the fact that his empire, like all successful large-scale states, had to accommodate the religious sensibilities of diverse populations. The guards who let the baskets pass may have been Muslim, Hindu, or of other backgrounds, but all recognized that interfering with religious offerings carried social costs. This cultural texture is often lost in accounts that emphasize only the confrontation between leaders.

The physical difficulty of hiding in a fruit basket for extended periods is rarely emphasized. Shivaji would have had to remain absolutely still and silent despite cramped, painful positioning, limited air, and the disorienting motion of being carried. The physical courage and endurance required—not in battle but in maintaining this uncomfortable concealment—was itself remarkable, yet it receives less attention than more conventionally dramatic forms of bravery.

Finally, the escape’s timing within Shivaji’s longer career deserves attention. At thirty-six, he was already an experienced military and political leader, not a young adventurer. He had already captured numerous forts, established administrative systems, and commanded significant forces. The decision to go to Agra—which led to his imprisonment and subsequent escape—represented a calculated risk that nearly destroyed him. That he recovered from this near-disaster and went on to even greater accomplishments speaks to resilience that goes beyond the escape itself.

The story of Shivaji’s escape from Agra remains one of history’s most compelling narratives—a tale of cleverness overcoming power, of individual courage against imperial authority, of a plan executed with precision under the most dangerous circumstances. Yet its true significance lies not in the escape itself but in what it enabled. Had those fruit baskets been inspected, had the guards been more vigilant, had any of a dozen elements gone wrong, Indian history would have followed a different path. The Maratha Empire might never have achieved the power and extent it eventually did. The challenge to Mughal authority might have ended differently. The political landscape of 18th century India would have been transformed.

Instead, the baskets passed through unexamined, and Shivaji reached home to continue building the kingdom that would eventually be formalized when he was crowned Chhatrapati at Raigad Fort. The man who escaped from Agra in 1666 became the emperor crowned in 1674, and the fruits of that escape—both literal and metaphorical—shaped the subcontinent for generations to come. In the end, perhaps that is the escape’s true legacy: not just one man’s freedom, but the birth of an empire that challenged the established order and demonstrated that power, in India as elsewhere, ultimately derives not from tradition or imperial decree but from the combination of vision, capability, and the will to claim sovereignty on one’s own terms.